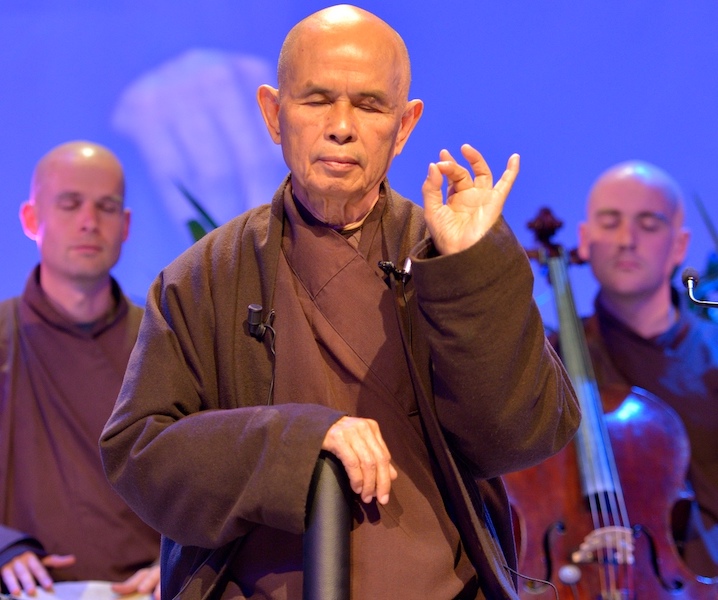

Questions and Answers with Thich Nhat Hanh

Stonehill College Retreat

August 16, 2007

Listen to the bell and breathe three times before you ask the question.

Child’s question: Why is the bell so important?

Thich Nhat Hanh: Why not? [Laughter] In the Zen tradition, sometimes we answer a question with another question.

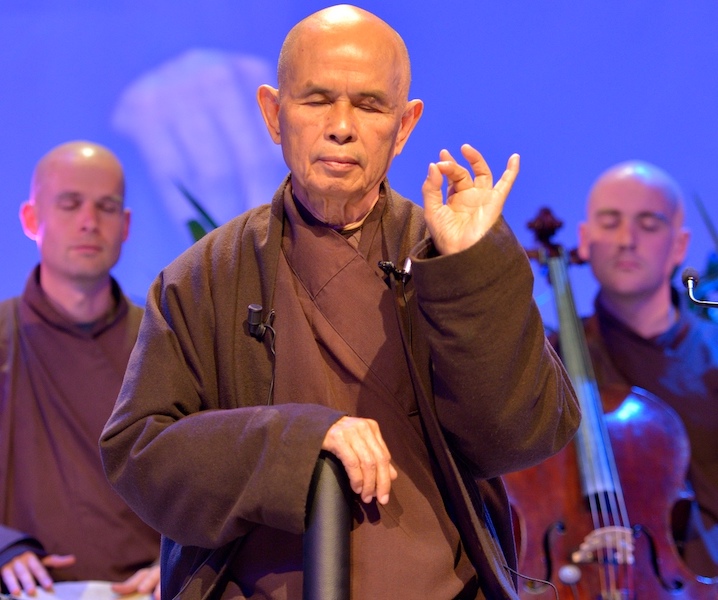

Questions and Answers with Thich Nhat Hanh

Stonehill College Retreat

August 16, 2007

Listen to the bell and breathe three times before you ask the question.

Child’s question: Why is the bell so important?

Thich Nhat Hanh: Why not? [Laughter] In the Zen tradition, sometimes we answer a question with another question. Very Zen! [Laughter] Thank you.

Child’s question: What do you do when you’re angry or scared?

Thay: When I am angry or scared, I go back to my breath and breathe deeply. I do not think anymore, I do not look anymore. I just bring my attention to my breathing in and out. I breathe deeply, and I calm myself. It always helps me. Every time I have an upset stomach, a feeling of unhappiness in my belly, I use a hot water bottle. And five minutes later, I feel much better. The same is true with mindful breathing. Every time we have anger or fear, if we know how to breathe, we apply our mindful breathing to that fear, to that anger. We embrace our fear and anger with the energy of mindful breathing. We get relief. It always works.

Child’s question: How can I control my temper?

Thay: As soon as you want to control it, there may be a fight going on between you and your temper. So it’s better not to try to control it, but instead to be with it and to take care of it. When you are angry or fearful, don’t fight your anger or your fear: instead, recognize it. Breathing in, I know I’m angry; breathing out, I recognize my anger and I take good care of my anger. You take care of it like a big brother taking care of his young brother or sister. It’s better not to fight. In the Buddhist tradition of meditation, there’s no fighting—just recognizing, embracing, helping.

Child’s question: Why are children born handicapped?

Thay: When a child is born handicapped, everyone suffers. The suffering is not the suffering of the child alone. The suffering is also the suffering of the father, the mother, the uncle, the brother, and the sister. If we look deeply, we see that happiness and suffering are not individual matters. We inter-are: you are me, and I am you. If something wonderful happens to one of us, it happens to all of us. If something awful happens to one of us, it happens to all of us. In that light, the child is the adult, and the adult is the child. We share the same kind of suffering, we share the same kind of happiness.

This answer comes from the Buddha’s teaching on the insight of no-self. With the insight of no-self, you see that this suffering is a collective suffering. With the insight of no-self, you see that this happiness, this joy, is a collective joy, collective happiness. We are not separated. We are linked to each other in such a way that your suffering is my suffering, and your happiness is my happiness. This is a very deep teaching of the Buddha. If you touch that wisdom, you don’t suffer anymore. You don’t feel cut off. You feel you are us, and we are you.

Hopefully, we will have the opportunity to learn more about the Dharma. The Dharma is wonderful. It can lead us from the notion of self and anger to happiness and interbeing.

Teenager’s question: What should you do if someone feels bad, and you want to comfort them and make them feel better?

Thay: You might like to practice the third mantra. You come to that person. You sit down peacefully and offer your friendship. You don’t try to do anything. You just say, “My dear friend, I know that you don’t feel well. I know that you suffer. That is why I’m here with you.” You offer your presence, which is fresh and loving. That is already something very important—your presence.

“Darling, I know you’re suffering. That is why I’m here for you.” Try, and you’ll see the effect.

Adult’s question: Dear Thay, with all the madness and violence going on in the world nowadays, how do you keep yourself from losing faith in humanity and giving up altogether?

Thay: There’s a practice called taking refuge. You want to feel safe and protected, you want to feel calm. If you don’t learn how to take refuge, you will lose your peace, your feeling of safety, and your calm. You will suffer, and you will make other people suffer. When the situation seems to be permanent, overwhelming, and full of suffering, you have to practice taking refuge in the Buddha—the Buddha in ourselves. Each of us has the seed of Buddhahood, the capacity of being calm, being understanding, being compassionate, and taking refuge in that island of safety within us. This is how we can maintain our humanness, our peace, and our hope. This practice is so important.

Practicing like this, you become an island of peace, of compassion, and you may inspire other people to do the same. It’s like a boat filled with people crossing the ocean: If they encounter a storm and everyone panics, the boat will capsize. But if there is one person in the boat who can remain calm, that person can inspire other people to be calm. And then there will be hope for the whole boatload. Who is that person who can stay calm in the situation of distress? In Mahayana Buddhism, that is you—you have to be that person. You’ll be the savior of all of us. This is a very strong practice, the practice of the bodhisattva, taking refuge.

In the situation of war and injustice, if you don’t practice like that, you will not survive. You will lose yourself very easily. And if you lose yourself, we have no hope. We count on you and your practice.

Adult’s question: How can we influence other members of our family, especially other adults, to avoid toxic inputs such as television shows, alcohol, etc.? Often, they are not interested in changing their lifestyle or in the practice. How can we handle this in our home?

Thay: The first thing you can do is to practice showing your happiness by smiling and being pleasant and fresh. That is a very convincing element. If you try to impose your ideas on them, you might get a strong reaction. You should not give a sermon; you should not blame. Just use skillful means to help them realize that breathing in toxins in their body and their mind will result in suffering. When you are practicing, taking good care of your body and your mind, and you’re healthy and smiling, when you are present—that is a live Dharma talk to them. Then you might use skillful means to help them indirectly.

There are young people who practice well and profit from the learning and the practice, and they do not dare ask their parents to practice like they do. The parent might say, “How can you teach us? You are just a little child.” So instead they use skillful means. For example, one child reported that they pretended to forget a book on the Dharma at home. And out of curiosity, the father picked up the book and read it. Another time, a teenager, a young lady, came to a retreat in Southern California, and her anger toward her father was deeply transformed. She returned home and was loving and fresh, and that inspired her father to attend the next retreat.

Things like that happen often. Your own transformation, your own peace and joy, will be the inspiration for other people to follow. And you have other skillful means to help people in your family be inspired to practice. You don’t say, “I practice, you don’t.

That is why you suffer!” [Laughter] That would be too irritating. You practice in such a way that they don’t see the practice. Your practice can be formless, and your transformation, your healing, will tell them about your practice.

Adult’s question: Aware of the suffering surrounding death, are we forced to see our loved ones as impersonal parts that are going to be reborn? Or is there a part of them as we know them, that will live on?

Thay: We have not been able to see ourselves or our loved ones deeply. Our understanding is still very artificial and shallow. We don’t know who we really are, we don’t know who they really are. That is why our notion of birth and death, of their presence and their non-presence, is also shallow. The practice of Buddhist meditation is to deepen your perception of what is there. When you know yourself deeply, you begin to know the people around you.

When you look at an orange tree, you see what it offers to us and the world: beautiful leaves, beautiful blossoms, beautiful oranges. A human being is like that too. In her daily life, she produces thoughts, speech, and action. Our thoughts may be beautiful, compassionate, and knowing. Our speech may be also compassionate, inspiring, full of love and understanding. Our action may be also compassionate, protecting, healing, and supporting.

Looking deeply into the present moment, you can see that we are producing thoughts, speech, and action, and we can know their value. In the Buddhist tradition, our thoughts, speech, and action are our true continuation. Once we have produced a thought, it will have an impact for a long time. When we say something, the message will have an effect long into the future. When we take an action, our action will have an impact for a long time.

Suppose you produce a thought of compassion and forgiveness. Right away, that thought has a healing effect on your body and your mind, and it has a healing effect on the world. It will continue to have a good effect in the future. It’s very important to be able to produce thoughts of compassion, nondiscrimination, forgiveness, and so on. You know that if you practice well, it’s not difficult to produce such a thought. That is your continuation: even if your body is destroyed, you continue on through your thoughts, your speech, and your action.

There are many people who believe that after the dissipation of this body, there is nothing left. Some of our scientists believe that. But our thoughts, our speech, and our action are the energy we produce, and they will continue for a long time. We can assure a beautiful continuation by producing good thoughts, good speech, and good action.

You cannot destroy a human being; you cannot reduce him or her to non-being. The other day, we said a cloud can never die. A cloud can only be transformed into rain or snow. A human being is also like this. You have to look deeply to see him or her beyond this body, beyond this feeling. It’s impossible for a cloud to die. It is impossible for a human being to become nothing.

When you look deeply like that into your true nature and the nature of people around you, you have the kind of insight that can liberate you from sorrow, fear, anger, and non-fear. It’s a great insight given to us by the practice of looking deeply.

Recently, we spoke about a wave going up and going down. As far as the wave is concerned, there is a beginning and an end, going up and going down. But the wave is at the same time water. And if the wave practices some meditation, she will realize that she is water. And when she knows that she is water, she will be smiling while going down. [Laughter] She will know she will not be passing from being into non-being. When you have that kind of insight and that kind of non-fear, you can inspire so many people, you can help so many people. You are truly a bodhisattva. You are no longer a victim of birth and death. You can ride on the waves of birth and death, smiling.

When we come to a retreat, we can learn practices that help us relieve some suffering. But the greatest relief you can get from the practice is from the insight that gives us non-fear, the insight of no-birth and no-death. Unfortunately, most of us are too busy making money, and we don’t have time to do that. You don’t have to become a monk, you don’t have to spend a lot of time in the meditation hall. You can live your daily life mindfully and deeply. Touching a cloud, touching a pebble, touching a flower, touching a child, deeply, you can touch the nature of no-birth and no-death. That is what the Buddha has achieved. That is what many generations of practitioners have achieved: they got freedom from fear, freedom from anger. They have enough happiness to share with other people.

Adult’s question: Dear Thay, first, thank you for helping me transform my life. Two years ago, I was here, extremely depressed and very anxious. I put a question in the bell, and I heard you answer me in your talk. You said that people feel a storm of the mind when they’re going through depression. Now that storm has subsided, I’m sitting up front, and I hear everything. It’s been wonderful. Thank you for helping me. My question is: One of my biggest fears in my life has been losing my mother or people in my family I feel close to. How can I transform this fear?

Thay: You can look deeply to see that our mother is not only out there, but in here. Our mother, our father, are fully present in every cell of our body. We carry them into the future. We can learn to talk to the father and the mother inside. I have done that several times, talking to my mother, my father, the ancestors in me. I know that I am only a continuation of them. I’m not a separate person, I am a continuation.

With that kind of insight, you know that even with the disintegration of the body of your mother outside, your mother still continues in you—especially in the energies that she has created in terms of thoughts, speech, and action. In Buddhism we call that energy karma. Karma means action: thinking, speaking, and doing. If you look deeply, you see the continuation of your mother in you and outside of you, because every thought, every word, every action of hers now continues with or without her body. Of course, you have to see her more deeply because she is not confined to her body. And you are also not confined to your body. It’s very important to see that. Every day we produce thoughts, speech, and action, and that is our continuation.

When I look at you, I see my continuation already. I see my continuation in my children, in my friends, and in the world. When I practice walking meditation, I want to make sure that every step of mine can bring stability, freedom, and joy. Every step like that is self-transformation to my friends and my disciples. I know they have received it. In this way, they bring me into the future. I’m not dying. Is it possible for me to die? This is the wonder of Buddhist meditation: with the practice of looking deeply, you can touch your own nature of no-birth and no-death. You touch the nature of no-birth and no-death of your father, your mother, in you and around you. Only that insight can reduce and remove the fear. Salvation not by faith, but by insight.

Adult’s question: Dear Venerable Thay, thank you for your light. I know oftentimes I struggle with judging, and I think I’m getting better with my tendency to judge other people. When I do judge other people, I’m always happy to be proven wrong. However, the hardest part about my judging is when I start to judge other people for their judgments—when I judge other people for what I believe is their being too judgmental. How can I overcome this type of judging of judging? [Laughter]

Thay: When you look at one person deeply enough, you can see that person is made of a lot of elements from society—education, parents, ancestors, culture, and so on. If you have not seen all these elements, you have not seen that person. If that person has the tendency to judge, it does not mean that she or he likes to judge, but has gotten the seed from many other sources.

When you see like that, you don’t suffer anymore. You may have compassion for him or for her. That person may be a victim of transmission. The negative things in him or her have been transmitted to him or her by society, by parents, by ancestors, or by culture. You are motivated by the desire to do something to change that environment and culture, so that the next generation will not be victims of it. In yourself, there is no anger; there is compassion and a strong energy—the desire to act with compassion. You don’t suffer anymore.

When you look deeply into yourself, and you notice some positive quality in you, you don’t feel pride because of this strength, talent, skillfulness, joy, or happiness. You know that you have inherited that from your ancestors, your parents, your culture, and so on. You are only a continuation of them. They have passed on these things to you. You are not arrogant about it.

If you see some negative things in you, like fear, anger, or discrimination, you don’t have a complex because you know that they have been transmitted to you by your parents and your ancestors. They were not able to transform these negative qualities so they have passed them on to you. If you have a chance to encounter the Dharma, you have a chance to transform, so that you will not transmit them to your children.

In both cases there is no judgment. There is only understanding, compassion, and the desire to act in order to transform.