By Sister Annabel Laity on

Sister Chân Đức teaches about Thích Nhất Hạnh’s lineage as a peace activist through his letters on the influence of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Father Daniel Berrigan, Mahātma Gandhi, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

The Vietnam War and Thầy’s activities for peace at that time may seem far away, but in fact, when we read about Thầy and other great peace activists of that era,

By Sister Annabel Laity on

Sister Chân Đức teaches about Thích Nhất Hạnh’s lineage as a peace activist through his letters on the influence of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Father Daniel Berrigan, Mahātma Gandhi, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

The Vietnam War and Thầy’s activities for peace at that time may seem far away, but in fact, when we read about Thầy and other great peace activists of that era, we realise that we just need to continue their work in somewhat different circumstances today. Racial discrimination still needs activists to confront it. Climate activists need to make their voices heard, and so the nonviolent struggle continues. Thầy has said:

People assassinated Mahātma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. hoping to reduce them to nothingness and remove them forever from this planet, without any trace left behind. How wrong they were! They are still there in each one of us, like immortal statues more vital and heroic than ever, because they continue in many different forms.

Without friends on the path, you are very lonely as a peace activist. In Vietnam while calling for peace, Thầy was opposed by those who had power in the Buddhist congregation and in the government. At the same time, he was supported by tens of thousands of young people, university students, intellectuals, writers, artists, and, from 1965 onwards, the Workers League. Thầy also found supporters in the West.

In 1966 Thầy returned to the United States to campaign for an end to the war in Vietnam. While on tour campaigning for peace, Thầy had a chance to make the acquaintance of many people who had a very open and progressive humanitarian view like Hannes de Graaf and Hebe Kohlbrugge in Holland, Heinz Kloppenburg and Martin Niemöller in Germany, Bertrand Russell and Philip Noel Baker in England, Danilo Dolci and Carlo Levi in Italy, André Trocmé in Switzerland, Paul Demiéville and Laurence Schwartz in France, Thomas Merton, Martin Luther King Jr., Daniel Berrigan, Dorothy Day, Arthur Miller, Robert Lowel, A. J. Mustee, and Alfred Hasslar, etc. in the United States, and Thầy learnt a great deal from their open and progressive way of looking that was completely in accord with the spirit of Buddhism.

Thích Nhất Hạnh in a letter to his monastic students

Martin Luther King Jr.

By the summer of 1965, there were 125,000 American soldiers on Vietnamese soil. Thầy and many leading Vietnamese intellectuals recognized the urgent need to muster global public opinion concerning the grievous state of affairs in Vietnam. Thầy and his colleagues were unanimous that Thầy write a letter to Martin Luther King Jr., asking for his support in speaking out to the North American people about the devastating situation in Vietnam. Thầy and his friends agreed that four additional letters should be written. Besides Thầy’s letter to Martin Luther King Jr., the Vietnamese writer, journalist, and politician Hồ Hữu Tường wrote a letter to Jean-Paul Sartre, the French philosopher and political activist. The poet and translator Bủi Giáng wrote to the most important French lyric poet of the twentieth century, René Char. The writer Tâm Ích wrote to the French writer and politician André Malraux, and the poet, writer, philosopher, and scholar Phạm Công Thiện wrote to the North American writer Henry Miller.

In writing to Martin Luther King Jr., Thầy said:

Nobody here wants the war. What is the war for, then? And whose is the war? Now in the confrontation of the big powers occurring in our country, hundreds and perhaps thousands of Vietnamese peasants and children lose their lives every day, and our land is unmercifully and tragically torn by a war which is already twenty years old. I am sure that since you have been engaged in one of the hardest struggles for equality and human rights, you are among those who understand fully, and who share with all their hearts, the indescribable suffering of the Vietnamese people. The world’s greatest humanists would not remain silent. You yourself cannot remain silent.1

Martin Luther King Jr. read the letter very carefully and, in 1965, he spoke out against the war and took part in the International Committee of Conscience on Vietnam.

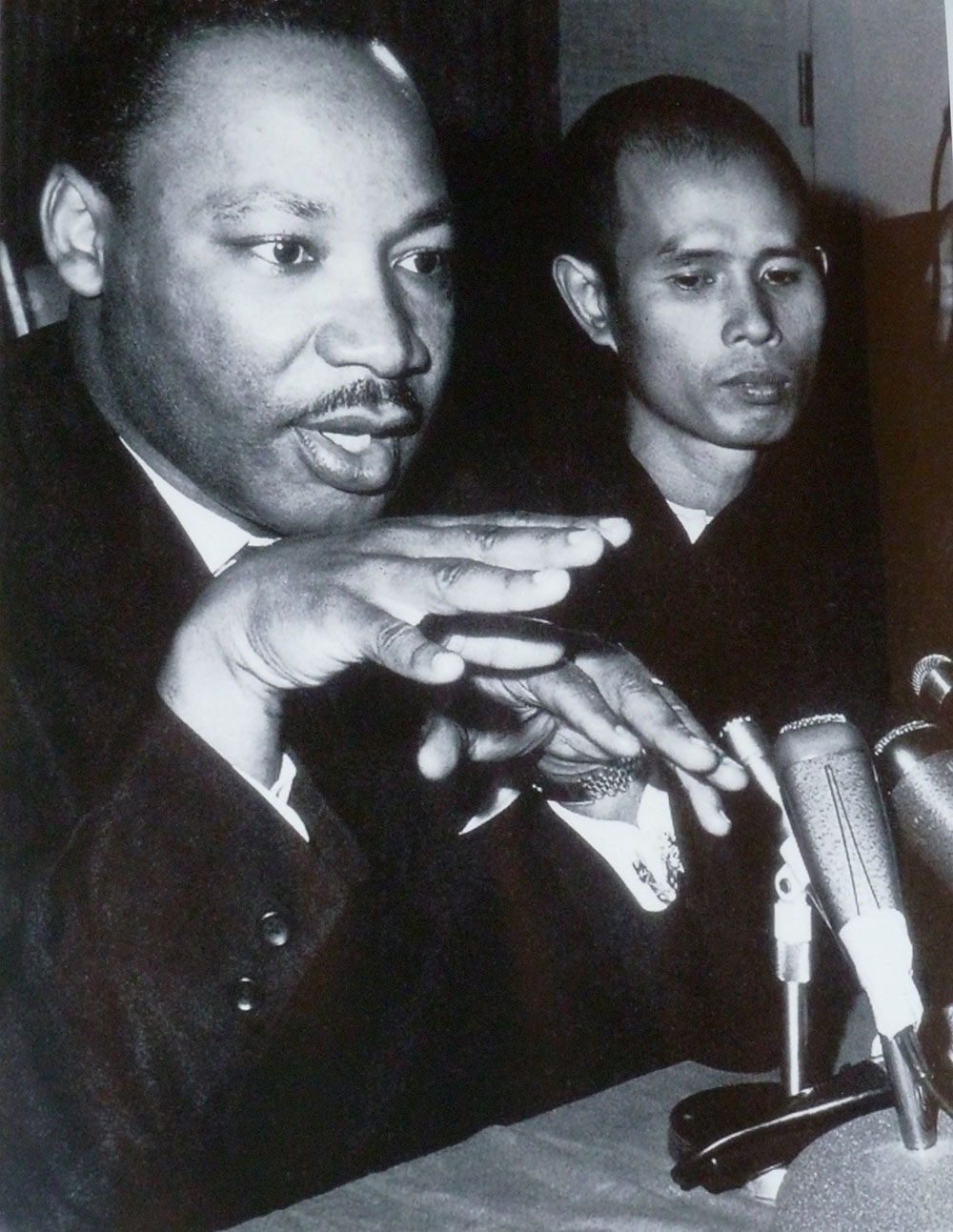

In May 1966, in Chicago, Thầy met Martin Luther King Jr. in person for the first time. They spoke for a long time about the Vietnam War. They then held a press conference in the Sheraton Hotel for about three hundred journalists. This was the first time Thầy had held such a large press conference. At the beginning of the conference, Martin Luther King Jr. and Thầy gave out a joint message:

We believe that the Buddhists who have sacrificed themselves, like the martyrs of the civil rights movement, do not aim at the injury of the oppressors, but only at changing their policies. The enemies of those struggling for freedom and democracy are not men. They are discrimination, dictatorship, greed, hatred, and violence, which lie within the hearts of man. These are the real enemies of man—not man himself.

We also believe that the struggles for equality and freedom in Birmingham, Selma, and Chicago as in Huế, Da Nang, and Saigon are aimed not at the domination of one people by another. They are aimed at self-determination, peaceful social change, and a better life for all human beings. And we believe that only in a world of peace can the work of construction, of building good societies everywhere, go forward.

On this occasion, Martin Luther King Jr. again publicly announced his opposition to the war in Vietnam. He asked everyone present to listen deeply to Thầy, who was representing people living under bombs and bullets.

When Thầy said goodbye to Martin Luther King Jr. before going on to Washington DC, he received a letter to read on the aeroplane. When Thầy opened the letter, he read:

Thầy Nhất Hạnh, I love you so much. I love your country so much. I do not know how to describe my feelings. I just wanted to hold you in my arms, but I did not dare to. I pray that you will realise all that you long for.

On April 4th, 1968, Thầy read the Heart Sutra during a Eucharist celebrated in Columbia University by Father Daniel Berrigan. After the ceremony, they went to listen to a lecture. The lecture was interrupted by the news that Dr. King had been assassinated. Thầy said years later:

I was devastated. I could not eat; I could not sleep. I made a deep vow to continue building what he called “the beloved community,” not only for myself but for him also. I have done what I promised to Martin Luther King Jr. and I think that I have always felt his support.1

The day after the assassination Thầy wrote a note to Ray Gould, who was a mutual friend of Thầy and Dr. King. Thầy wrote:

Ray, send me the picture in which you and I and he were together. I want to see again the expression of his face when he told me in summer 1966 when we were in Chicago:

“I feel compelled to do anything to help stop this war.” He made so great an impression on me. This morning I have the feeling that I cannot bear the loss.1

In the same letter Thầy said he was a little comforted by the fact that in Geneva, when he met Martin Luther King Jr. for the last time, Thầy had said:

Martin, do you know something? The peasants in Vietnam know all about what you have been doing to help the poor people here and to stop the war in Vietnam. They consider you as a bodhisattva.1

Father Daniel Berrigan

This is what Thầy told his students in 2014 about his friend Father Daniel Berrigan:

He is a Jesuit priest living in New York. He is very famous and this year is ninety-three years old, a writer, and a poet. When I met him, it was in 1968 when I was campaigning for an end to the war in Vietnam. He was a peace activist. We became friends and had long discussions about war and peace. Father Berrigan came to France and stayed with us for three months to practise mindfulness. He practised sitting and walking meditation and looking deeply. Every day we sat together to exchange our experience of the practice. He brought a tape recorder with him and recorded all the conversations we had.

When he returned to the US, he wrote a book authored by Daniel Berrigan and Thích Nhất Hạnh entitled The Raft is Not the Shore. The raft is the means to go to the other shore, but it is not the other shore. This book is still in print, but I do not know if it has been translated into Vietnamese.

When I first met him, he did not know about walking meditation. One day I invited him to go for a walk in Central Park, New York. I said:

“We are not supposed to talk. We just walk in order to walk.”

Father Berrigan was much taller than I. His legs were long, so for every one of his steps I took two. We both started walking together, and two or three minutes later he had left me ten metres behind. Seeing I was no longer alongside him, he stopped and waited. I was not in a hurry. I walked along slowly at my own pace. I was determined to do that, because I knew if I did not stick firmly to the practice, I should lose myself like others in this society where everyone is in a hurry. I was determined to use my steps and my breath in order not to be swept away by the North American society.

After that Father Berrigan came to France to practise and learnt how to walk slowly in meditation correctly.

In 1968 Father Daniel Berrigan, along with his brother Father Philip Berrigan and other Catholics, was imprisoned for burning draft files in protest at the war in Vietnam. When criticised for this action Father Daniel said: “It is better to burn paper than children.”

In 1980, Daniel and Philip Berrigan, along with six others, began the Ploughshares Movement to demonstrate against nuclear weapons, inspired by the words of the prophets. After hammering nuclear missiles and submarines into ploughshares and using their own blood to pour on documents and weapons, they faced many years of imprisonment.

There is a deep connection between spirituality and activism. Thầy often spoke of mindfulness as holiness or the equivalent of the Holy Spirit. When put on trial for trespassing, entering security areas, or doing damage to property, members of the Ploughshares Movement would talk of being led by the Holy Spirit.

Ploughshares activist Art Laffin said, “People who have been involved in ploughshares actions have undertaken a process of intense spiritual preparation, nonviolence training, and community formation and have given careful consideration to the risks involved.”2

In 1974 Father Daniel said of his visit to Thầy and the community in Sceaux: “I was being healed of America, of the Western Church, of the Jesuits, of the wounds of war, of the disease of making it, of my race in time against time.”3 For his peace activism, Father Berrigan received severe criticism from his own church.

In 2010 Thầy told of a dream he had had about Father Berrigan. A letter of birthday greetings was sent to Father Berrigan recounting the content of the dream. Thầy did not write the letter himself, but recounted the dream to his attendant, who wrote the letter:

In a dream Thầy saw his friend Father Daniel Berrigan. Sitting next to this courageous priest, Thầy recognized that he was worthy of all respect and reverence. Thầy suggested that the community touch the earth before him…. Suddenly Thầy saw that he was sitting alone with Father Berrigan and he opened his arms to embrace Thầy. Thầy also opened his arms to embrace his friend in the true spirit of the Plum Village practice of hugging meditation. At first there was only happiness and the peace of brotherhood, but soon an unsettled energy arose in Thầy… the energy of sadness, pain, and loneliness. Thầy felt clearly that the other person was receiving this energy and responding to it…. Waking up, Thầy knew the dream had helped his own well-being, because he’d had the opportunity to recognize and share his sadness and pain with a dear friend who had the capacity to touch and understand that sadness and pain, having gone through similar difficulties, sadness, and loneliness. Thầy thinks that in our lives, those with whom we can share like this are few, even within our own tradition.4

Mahātma Gandhi

Thầy often referred to Mahātma Gandhi in his teachings, especially in his teachings about the Mindfulness Trainings:

Mahātma Gandhi lived like a monk in terms of food, clothing, and sex. If he didn’t live as a monk, he would not have enough energy to lead such a sacred struggle (against the British Empire). Mahātma Gandhi said to his wife, “In this struggle, I need to have enough energy, so we must forgo having sexual relations.” And Mrs. Gandhi said, “I understand, please follow your path.”5

Thầy spoke of Gandhi in relation to the First of The Five Mindfulness Trainings and the Second of The Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings. Gandhi said: “In my search after truth I have discarded many ideas and learned many new things.” Thầy said the Mahātma had the spirit of non-attachment to views and, although he was not a Buddhist, was never caught in what he already knew. Gandhi also said: “Old as, I am in age I have no feeling that I have ceased to grow inwardly or that my growth will stop at the dissolution of the flesh.”

One time the Mahātma said to Jawaharlal Nehru, who often differed from Gandhi in his point of view: “Resist me always when my suggestion does not appeal to your head or heart. I shall not love you the less for that resistance.”

With regard to the Second of The Five Mindfulness Trainings, Thầy also quoted Gandhi:

Our ancestors set a limit to our indulgences. They saw that happiness was largely a mental condition. A man is not necessarily happy because he is rich or unhappy because he is poor. Observing all this our ancestors dissuaded us from luxury and pleasures. The mind is a restless bird; the more it gets, the more it wants and still remains unsatisfied.

When referring to The Simile of the Saw Sutta (MN 21), Thầy said:

In this sutta the Buddha says that if we can master our body, our mind and our anger, even if someone saws our limbs into pieces we can still remain sovereign of ourselves. We see that that person is just the victim of their ignorance and hatred. This is an example of extreme nonviolence, like when Mahātma Gandhi launched the nonviolent movement to resist the violence of the British government and to struggle for the independence of India. People in that movement were beaten and killed, but they remained peaceful and did not return violence for violence.

Thầy often referred to the words of the Mahātma: “My life is my message,” and said that the Mahātma did the things that he taught. If we do not do what we teach, our teachings have no meaning.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

In November 1962, while staying in New York, there was a night Thầy could not sleep. In the middle of the night, he rose and read what Bonhoeffer had written during his final days in the prison of a concentration camp. Bonhoeffer’s peace, compassion, and courage deeply moved Thầy:

[The account] of the final days of Bonhoeffer’s life helped me suddenly to wake up to a sky full of bright stars that is there in everyone. I felt strangely happy, and knew that I had the ability to withstand. Bonhoeffer was the drop that made my cup full to the brim, the last condition, the light breeze that made the ripe fruit fall. After experiencing such a night, I will never complain about life again…. Life is miraculous, even in its suffering. Without suffering, life would not be possible.

Bonhoeffer said that when he was put on trial by the Nazis and in prison he learned that there is a great difference between a theologian and a Christian.

Thanks to Bonhoeffer’s extraordinary virtue and courage, Thầy recognized the presence of bodhisattvas on the Earth and not just in the sutras. For the whole of the following month, Thầy meditated on the bodhisattvas in the Lotus and Perfected Wisdom Sutras. Thầy saw that bodhisattvas were people whom we could encounter in this life and they included the young people in Vietnam whom Thầy was guiding.

Thầy has said that people like Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi are Mahasattvas, great bodhisattvas, while we are Hinasattvas, little bodhisattvas. Great bodhisattvas and little bodhisattvas interare. The great bodhisattvas encourage and inspire the little bodhisattvas on the path of nonviolent resistance. As little bodhisattvas, we know that hatred can never put an end to hatred, and so we vow in our daily lives to remember the lives of these great bodhisattvas. In this way, we shall have the courage to go ahead in the great global nonviolent struggle.

1 Tăng thân Làng Mai, Đi gặp mùa xuân: Hành trạng Thiền sư Thích Nhất Hạnh, (Hà Nội: Thái Hà, 2022)

2 Art Laffin, 2019, “A History of the Plowshares Movement – a talk by Art Laffin, October 22, 2019,” The Nuclear Resister.

3 Jim Forest, Eyes of Compassion, (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2021)

4 Marc Andrus, Brothers in the Beloved Community, (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2021)

5 Thích Nhất Hạnh, 2010, “Attadanda Sutta (Part IV),” Thích Nhất Hạnh Dharma Talks.