Separation to Inclusion

By rehena Harilall

I was born in South Africa during apartheid, with African and Indian heritage in a lineage of slavery and indentured labour. I grew up in a segregated Indian area to a family who lived in a tin house with no electricity, from which we were forcibly removed to make way for white people’s housing.

Separation to Inclusion

By rehena Harilall

I was born in South Africa during apartheid, with African and Indian heritage in a lineage of slavery and indentured labour. I grew up in a segregated Indian area to a family who lived in a tin house with no electricity, from which we were forcibly removed to make way for white people’s housing. My childhood was full of colour and nature: green trees, blue seas, bright shining sun and people in all shades of brown.

I grew up feeling both fear and attraction to white people—fear that they had the power to control where I lived, studied and socialized. They could take away my possessions and loved ones any time with no need for justification. At the same time, I wanted to be white. Then I would have access to the best jobs, could choose where to live and go where I pleased whenever I wanted. This would make my family and me very happy.

I was angry with myself for not being as beautiful as my blue-eyed, pink-skinned, blonde-haired doll, and with the injustice of people and society that created and fostered from racial oppression and thrived from it. I became an activist, fighting for equality and to ‘overthrow oppressive regime,’ a cause I was willing to die for. I also did my utmost to become as white as possible, hoping my skin colour would be overlooked and I could gain access to things that would make me happy. If I could fit in, speak properly and not wear Indian clothes, maybe they would realise I was not a backward coolie (laborer) or kerrikop (curry head), that I was almost one of them. Then I would be so happy.

I first came to the United Kingdom in 1998, after democratic elections in South Africa, as a result of my socio-political change work. There, I saw white cleaners and white people digging streets. ‘Yes,’ I thought to myself. ‘Here are the British values; equality, justice and meritocracy.’ I would no longer have to be ten times better to be accepted as equal. I was now part of the ‘privileged’ group with access to conditions and possessions that would make me happy. I could live where I wanted, eat in any restaurant and buy anything. My cleaner could be white.

It did not take long to see exclusion was still present in the UK. The class system created privileges for the few at the expense of many. Racism was veiled and difficult to pinpoint, and therefore even more corrosive. My exotic name and brown skin often led to my being paid less or overlooked for promotions. Perhaps, I thought, if I changed my name and became more western; if I learned a European language or kept updated on the latest fashions, labels and gadgets; if I worked and tried harder, perhaps I would fit in and be accepted. But the rules kept changing.

Suddenly, the traditions I once had been told that were backward, like yoga and chanting, were being sold to me by white people. Indian food was fashionable and was being marketed to me by ‘white experts,’ who started adopting Indian dress and names. I was angry, disillusioned and hurt. I was still no closer to being happy. The never-ending cycle of working harder and keeping up with the latest gadgets and trends was Sisyphean. The harder I worked to fit in, the more I suffered, and so did everyone around me.

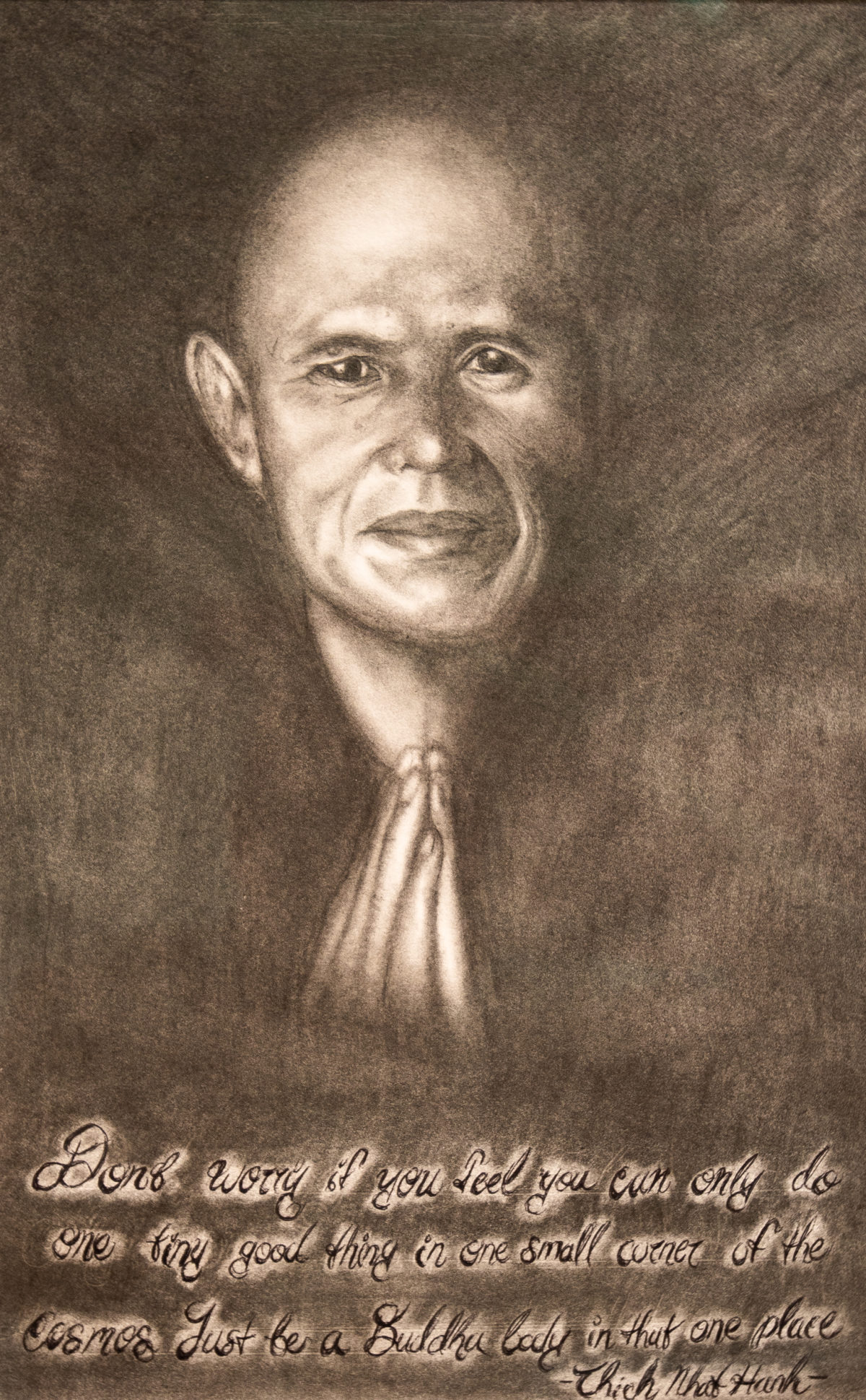

Then, a friend introduced me to Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings. I was drawn to his radiant peacefulness and compassion. Here was someone who, despite his experiences of war and conflict in Vietnam, was happy. I wanted this too.

Simply breathing set the foundations for my healing and helped me see my suffering. As I sat and walked, I started seeing how my feelings of exclusion and desire to belong permeated my actions, thoughts and perceptions. I started realising how much I was trying to fit in and earn my place in a group. Through practice, I saw how much I worked to not be rejected and to cover up my shame for being unworthy.

Through mindful breathing and walking, I am learning to take care of anger that manifests in me at any hint of discrimination and exclusion. I am learning to see that my anger is how I try to protect myself from pain and suffering. Listening to my anger and feeling where it manifests in my body helps me take care of it. Sometimes my anger needs spaciousness, and I take her for a walk. Sometimes she needs love and compassion. As my ability to embrace and hold my anger with love and compassion grows, my compassion for those who make me suffer grows too. I see their anger is also fuelled by pain and suffering.

While working on a Sangha project earlier this year, I grew angry because someone started taking over my tasks, making decisions without involving me, telling me what to do and not responding to my emails. My tree of exclusion bloomed red flowers; I got very angry. I took my anger for a walk and saw that my old suffering had emerged—the pain of not feeling heard, not being good enough and being excluded. Giving myself spaciousness to look deeply helped me realise my withdrawal from the project would be best. My feelings, still burning and painful, could easily be triggered and cause harm. A few weeks later, I was strong enough to offer the other person compassion and gratitude for all the times they had helped me in the past. As I did this, my anger dissipated.

My practice has helped me look deeply into the pain of exclusion I carry. I see it is also the pain of my ancestors. In trying so hard to fit in, I was separated from my body, which I only realised after several months of chronic pain. My gruelling exercise regime was driven by anger rather than love for my body. Exercise was punishment for not being like my slim, blue-eyed, light-skinned doll.

Now, after nine months of sitting with and offering gratitude to my pain, I see the beauty of the earth in it. A woman I met told me that when she was growing up, her grandmother told her, ‘You are loved so much. That is why you are the colour of the earth, and if you look closely, you will see the sun under your skin.’ Now, I see the gold glinting in the folds of my skin in the sunshine; I see the emeralds and rubies too. When I look deeply, I see the strength and power of the earth there.

Inclusion starts within me. It starts with making myself whole again. I don’t have to be white to be happy. I can be brown and be happy. I can look at my skin and see the earth and look at the earth and see my skin. The source of my happiness is myself. I don’t need to fit in when I can belong to myself.

Reconnecting with my ancestors through Touching the Earth practice is helping me reconnect with aspects of my history and the lineage I have rejected and suppressed. Inclusion is forging connections with my body, culture, traditions and ancestry. I connect with all my ancestors: Indian, African and white. I see ancestors who come from Gaya, those who drummed to hear the sound of rain on the earth, those who sold themselves to labour to seek a better life and those who wielded power to hurt—oppressed and oppressor.

I am learning to accept them all. Learning to wear Indian clothes again and drumming to the Earth’s heartbeat strengthens my connection with ancestors. I no longer feel weighed down by the burden of my ancestors, but I feel I am like a leaf held up by strong, broad trunks and deep, deep roots. I accept that the qualities of strength and fortitude, alongside unskilful habits, have been transmitted to me. Acknowledging my ancestors and recognizing their qualities in me helps me be more compassionate and kind. I have seeds of discrimination and racism transmitted to me; how can I be angry with others who have the same seeds?

Going to a people of colour space supports my healing. And healing the historical dimension helps me touch aspects of the ultimate dimension. I see that peace, social justice and equality begin within me. Fighting injustice from anger creates more division, not peace. Inclusion is about accepting even those whose views diverge from mine.

Every day I try to communicate more peacefully with those I disagree with. I see being kind to myself is helping me be kind to others. Seeing my own suffering helps me see the suffering in others.

Having happiness and peace does not require me to work hard to fit in, to change myself or to become someone else. Dr. Cornell West said, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” I think inclusion is how we show love. My skin colour is a daily reminder that, like the earth, I can be peaceful and embrace all views and myself.

rehena Harilall, True Deep Source, was born and lived in South Africa. Since 1998, she has lived in the UK, practising Thay’s teachings. She joined the Order of Interbeing in 2016, and practices with the Heart of London Sangha and Colours of Compassion Sangha.