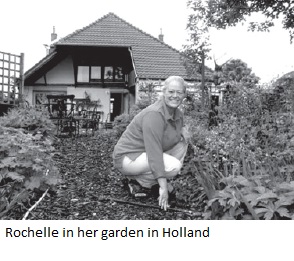

An Interview with Rochelle Griffin

by Barbara Casey, at Plum Village, June 2002

Barbara: Rochelle, how did you come to live in Holland?

Rochelle: I was born and raised in the United States. During my first year of college my father became the director of the American International School in the Netherlands. So the next summer I went to Holland for vacation.

An Interview with Rochelle Griffin

by Barbara Casey, at Plum Village, June 2002

Barbara: Rochelle, how did you come to live in Holland?

Rochelle: I was born and raised in the United States. During my first year of college my father became the director of the American International School in the Netherlands. So the next summer I went to Holland for vacation. I decided to stay a year, and then I never returned to the U.S. I was a very angry young woman, and I was particularly angry about America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. I had many friends who had gone to Sweden or to Canada to avoid the draft, and I felt a lot of solidarity with them.

I was also scared, because in the United States they had shot students who were protesting the war at Kent State University. In Europe I had such a sense of solidity from the culture, from the cities and cathedrals that were a thousand years old. I liked Holland because it’s a very small country that has integrated many cultures and many religions, and I really appreciated that there were fifty-two political parties. It’s a socialist government and somehow the people are able to work together. There were a lot of anti-war demonstrations, and I had no fear when participating. I found work and friends in Holland. So I’m American by birth and Dutch by choice!

Barbara: Tell us a little about the work that you are doing now.

Rochelle: The story starts many years ago when I was in training to become a midwife. I was critically injured in a car accident in 1980, the only survivor of a front-on collision. I was in the hospital and rehabilitation for almost two years. There were a number of times that I didn’t think I was going to survive. I have a clear memory of a near-death experience that changed my outlook on what I perceived death and life to be. During this experience I was not attached to my body, and I had a deep experience of being pain free, of being surrounded by a sense of well-being, support, love, and life. I felt that I had a choice to go towards the light or to return to my body. I was able to bring back that deep awakening with me when I returned to consciousness. I had a real sense that I had work still to do on earth.

That experience helped me begin to learn to live with chronic pain. As I started to deal with chronic physical pain I realized I also carried a lot of chronic emotional pain. At this time I met Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who is a well-known Swiss-American psychiatrist and has done a lot of work dealing with the taboos around death and dying. I was her translator during a workshop called “Life, Death and Transition.” I felt very strongly that my new work would be helping people process their suffering. I spent much of the time between 1984 to 1988 in the United States and Europe, doing workshops and training with Elisabeth and her staff. Because of my accident and resulting handicaps, I received disability pay from the government. I did not want that kind of financial support, I wanted to be independent and self-supporting. But in hindsight it’s been a blessing because it’s given me the freedom to develop the work I’m doing now.

In 1985 I started working primarily with people with HIV and AIDS in the Netherlands. I didn’t decide to work with these people in particular, but it was the group that was calling me and the door that opened. It was such an honor to be with people who had been afflicted with great suffering very young in life, and to witness their process of healing before they died. Their suffering included a great deal of stigmatization and misunderstanding and I have always felt an affinity to those issues.

In the beginning I worked primarily with gay men, but before long there were many people of mixed backgrounds including college students, middle aged women who were infected through their husbands, people using drugs intravenously, prostitutes, people in prisons, and people who had sex with someone who was infected. There were also children who were infected during birth and those who were orphans, because both parents were ill or had died of AIDS. Before there was any medication for treatment (AZT only became available in 1987,) I mostly worked with death and dying issues because people had an average life expectancy of only about thirteen months after diagnosis. Later as more medications became available, we were able to work through much of the pain and suffering at a deeper level through our Homecoming workshops, and to nourish the resulting peacefulness with mindfulness retreats.

In 1989 I set up my own foundation, called Fire Butterfly Foundation for Conscious Living and Dying. “The butterfly is a universal symbol of the soul freed from the confinement of the body. Fire stands for the accelerated transformation process which occurs when we’re confronted with our own impending death. People with a limited life expectancy can meet this challenge and increase the quality of their own lives and of those around them in a powerful and positive manner.” Rochelle Griffin

I feel that I have become a midwife in other phases of life, and am often a midwife for men too! My work has to do with finding out who we really are deep inside. In doing so we can discover that we’re really not as isolated and as alienated as we may have felt through our upbringing, that there is an energy in us that connects us as human beings to each other and to the universe. I wanted the groups to be mixed with young and old, gay and not-gay, men and women, and parents with children. Also caregivers would come to the workshop thinking it was going to be five days of lecture, but all this work is experiential, and that is what really helps to be a better caregiver. You can help others better when you understand that you’re not alone. When you’ve worked through your own feelings of anger, fear, grief, hopelessness, and helplessness, then you can be with others as they experience their own pain and suffering, without interrupting their process and without offering solutions. I don’t think that you can actually accompany people on this path futher than you have dared to go yourself. In trusting this process, we can tune into a different level of knowing what is best for us from inside out. And then we can trust that others will find their own way too, and we can be there for them, keep them safe, and encourage them to find their own answers.

In about 1982, a friend suggested that it might be helpful for me to learn to deal with my chronic physical pain by learning some form of meditation practice. I enrolled in a weekend retreat in a Christian abbey where Zen was practiced, and in that first weekend I discovered that instead of denying pain it was possible to go right into the heart of the pain and to sit in it. The pain transformed, and there came a great space where pain was present but it wasn’t only my pain, there was a sense of collective supportive energy. I also realized that my pain increased by resisting it and trying to deal with it alone. I practiced on this path for about fifteen years before I found Thay.

Barbara: Can you give us an example of some of the processes you offer in your Homecoming workshops?

Rochelle: People come to me when they find out they’re ill, usually. Or there are families, or healthcare givers, for instance, who are dealing with burn out. To prepare for a workshop, which is a very deep experience, we ask for a lot of medical information and we also do an extensive professional intake, so that we know who’s coming and if it’s appropriate for them to attend.

Usually the workshops have about fifteen to twenty-five participants and two to three staff members. It’s a very mixed group. I don’t work exclusively with people with AIDS any more because many of the doctors and healthcare services in Holland are referring people with other diseases and people with war trauma, abandonment or sexual, physical, and emotional abuse issues. Everyone seeking their own answers in dealing with issues related to loss and change are welcome to apply.

People will come thinking, “I’m coming to learn how to die,” or “I’m coming to learn how to live,” but they discover that they’ve been carrying a kind of backpack around almost all their lives they feel a weight on their shoulders that they can’t explain, so bit by bit we take some of the stuff out of that backpack and look at it. We bring the dark parts into the light and in doing so, we discover that we were actually more dead than alive by carrying this weight around! As a facilitator, my primary job is to create a physically and emotionally safe environment for this to happen.

In the beginning of the workshop we set a number of agreements about how we’ll be together, about confidentiality and how it’s okay to share our feelings, to be angry, to cry, to feel fear and express it by screaming, for instance, and it’s also okay to be quiet. We begin expressing feelings gradually, but because it’s a group process it goes very quickly but quite deep.

The first evening we have a candlelight memorial ceremony for the many losses that we have had in our lives. People just say a word or a name as they’re lighting a candle. The next morning we do some teaching around what we consider natural emotions that we are born with and enable us to survive in the world, and we teach how they become distorted in our lives, often causing more suffering. That is our ‘unfinished business.’ For example, there was a man recently who was feeling a great deal of fear and there’s nothing more scary than working with fear. I invited him to come forward and I explained: We work only with that what is present in this moment, so if you feel ready to explore this, sit down here and tell me what you’re feeling in your body, because we always start with the body. I started with a relaxation and guided meditation with awareness of breathing. The body gives us a lot of information, it’s as though the cells have a memory. This man shared that he felt as though there was a brick in his belly, it was really hard and black on the outside and bright red inside and less solid. This gave me some indication that there might be a layer of fear (the hard outer layer). The blackness could represent grief, surrounding a lot of anger represented by the inner, red, more fluid part, telling me that it could be explosive and dangerous if released unexpectedly. He told his story of having been a Spanish immigrant child, living in Germany with his family. He was left alone a lot of the time. His father was unhappy with his work and he’d become an alcoholic. His mother worked as a cleaning lady, and was away much of the time. The mother and children were abused by the father when he was drunk. This kid spent more and more time on the street, got involved in a gang to feel that he belonged somewhere and was caught dealing drugs. He was sent to jail, and in jail he was raped, and in the process he was infected with HIV. He had so much fear about getting into his feelings because he thought, If I really get into my feelings I’ll kill someone, and I don’t want to kill people, I don’t want to continue this vicious cycle, I want to stop it!

I explained: This mattress we are sitting on is the boundary, this is where you can get out all your rage and your grief, step by step. Gradually he opened into his deepest feelings and he got into some very deep rage, and what he found beyond that rage was the little child that he’d been when he was three years old. Discovering this child, he sobbed deeply. At three years old, he had been taken care of by his grandmother in Spain while his parents went to Germany to work. She was his security and his love, but she died, and he had to go to Germany to be with his mom and dad, and as the family became increasingly dysfunctional, he was hurt very much in many ways. But when he was able to get into contact with that little child in himself, he again felt the joy and peace that he’d missed for a long time. He came to understand some of the ways that he had learned to neglect and abuse that child, which empowered him to take charge of his life. He began to understand that his parents had done the best they could under the circumstances. Eventually he was able to forgive his parents and himself.

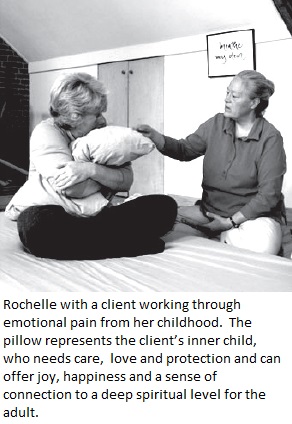

I have found that this work of dealing with our feelings in a very direct way helps us to connect with our ancestors and connect with our spiritual self. We’re not teaching people to beat on telephone books or pillows continually. Sometimes people might need to do that a couple times just to get a sense that they can be angry without getting to the point that they will kill someone. In this way they learn the difference between healthy anger which enables us to say ‘no’, to be assertive and set limits, and distorted anger when we can hurt ourselves and our loved ones. I’ve worked with quite a few war veterans and people in prisons who have killed people, to help them understand that deeper inside there’s a very wounded child who needs to be healed and cared for. When we can access that child, the healing occurs, and the forgiveness develops. I think forgiveness, including self-forgiveness is a very important issue.

Barbara: Do you use conscious breathing in this process?

Rochelle: I do help people to become aware of their breathing how deep, how free it might be in a particular moment. The breath is a key tool that can be used to access the body and to understand what is going on inside, beyond the thinking. I’m very skilled in observing body language.

In the Homecoming workshop we present this work through a form of Gestalt therapy, which is a mixture of a number of psychotherapy techniques. It’s based in healing wounds so that we can come to a place of peace and joy, so that we can live our life with a sense of aliveness instead of merely surviving. Breathing is a real tool. I often will tune in to someone’s breath to understand more deeply where he or she is emotionally at that moment. Our breathing tells us a lot. I become aware of my breathing to see where it’s stopping or where it’s flowing or if it’s smooth or not smooth, kind of like taking my emotional temperature. I explore the places in my body asking for attention (by being painful, closed, restricted, cold, or empty) during my in-breath and offer space and relaxation with the out-breath. In the workshops we begin and end the day with mindfulness meditation, and do walking and sitting meditation with the participants. In the workshop we also demonstrate how we can effectively become better caregivers. If someone has survived and transformed a certain experience of suffering, others can be nourished when that story is witnessed and understood.

Conscious breathing plays a role in the workshops as it does in the dying process. When people become more ill and closer to death, mindful breathing becomes more and more conscious, because when you have no energy, what else can you do but breathe? Through your breathing, you can connect to your emotions, as a way of releasing, letting go, and relaxing. Also as a way of connecting to what is and to that which we are holding on to and avoiding.

This last winter I was very ill with pneumonia and was having a hard time breathing, and I was so grateful that I know how to connect with my breathing through mindfulness practice. From my window in the intensive care unit in the hospital I could just see a small strip of sky between the buildings. I noticed the full moon outside and in this way I connected with my loved ones, and flowed with the pain, not denying anything, but able to connect with love, with life, and with support. I felt completely safe and at one with the universe.

Often people from one of my workshops will ask me to be with them or guide them in their dying process. One of the greatest fears that we have is the fear of dying alone. I don’t think we actually can die alone, but people often fear that they might. So I offer my service of being with them as they prepare to die.

Barbara: What do you mean when you say that you don’t believe that we can die alone?

Rochelle: I feel that we have a lot of help from both sides people with us in the present as well as from the collective consciousness. Often I hear stories from people who have been close to death, who say that a loved one who has already died is present, that their essence is present somehow during the dying process, and that this eases the fear and even can increase the sense of joy and peace in going towards death.

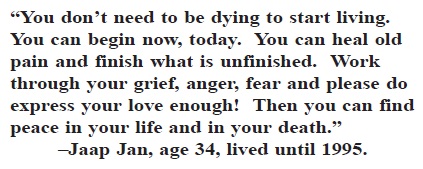

Often I will ask someone who is dying, “What do I tell people who want to know about dying? What is your message, your truth that you would like me to share?” The answer is always similar to how one friend expressed it: “You don’t need to be dying to start living. You can begin now, today. You can heal old pain and finish what is unfinished. Work through your grief, anger, fear and please do express your love enough! Then you can find peace in your life and in your death.” – Jaap Jan, age 34, lived until 1995.

Barbara: As mindfulness practitioners, how can we best be with our loved ones who are ill or dying?

Rochelle: Mindfulness practice is so important because it makes us aware of the moment and of being present, and what sabotages us from being truly present. It can be real hard when it’s your own family member, especially when we have unfinished business, expectations, and unfulfilled longing.

We can learn to be instruments of peace. If we are firmly rooted on the earth, with our head touching the sky, connected to our source of spirituality in the universe, we can be an instrument between the universe and earth. Being peace in ourselves, making peace in our family and community, then we can facilitate the peace process with others. Understanding the breathing is a real tool because dying is not much else than a deep and total relaxation!

Barbara: At retreats we do semi-totally relaxation!

Rochelle: As long as we’re alive we don’t do that quite so totally as when we die!

Barbara: Right, right.

Rochelle:When we come into this world, we fill our lungs with breath, and this is the point of birth. At the end of life we breathe out and we die. I often offer breathing exercises and relaxation exercises to people going through the dying process. If you put a little more accent on the out-breath and it becomes a little bit longer, there is a point when there’s no breath, a still point. The in-breath is effort, and the out-breath is the relaxation or letting go.

Often I meet people who are so concerned about life after this life, or life before this life. I feel we have our hands full with our suffering and our joy in this life! I sometimes wonder if we actually are able to experience life before we die. Many people seem just to be coping to survive, without feeling really alive. So what I do is to bring what we experience as painful and that which we deny or run away from, into our consciousness so that it can heal.

I’ll tell you a story about a really good friend of mine who died a few years ago. He had to have lung surgery, and he’d asked me to be present while he went through this. I stayed with him for the weekend afterwards. He was in and out of consciousness, and every time he became conscious he would grab my hand and not want to let go. But as he would relax and kind of slip away, I let go. I stayed in a very light physical contact with him with my little finger just touching his, but not with the grasping. And I continued to breathe with him. I would support his breathing with my breath by making it a little audible.

As he came around and awakened, he said, “Rochelle, your being here has felt very supportive, but why did you keep letting go of my hand?”

I explained, “I wasn’t sure if it was your time to go, and I wanted you to feel free. I wanted to be present with you, whichever way you needed to go.”

“Oh,” he said, “I understand. I was grasping.” And I said, “Yes, and I wanted you to know that you had the choice, the courage, and the freedom to do what you needed to do for yourself.”

A few months later he was near death, and I went to the hospital, as he was asking for me. This was Saturday morning and the plan had been for him to go home on Monday so he would be able die at home, probably later that same week. But he was becoming very weak and his breathing was labored. I came into the room I looked at him and he looked at me, and I said, “You know, you are going home.” And he nodded. He knew. I added, “But, we cannot take you to your house, do you understand that?” And he nodded again. He had an oxygen mask on. I asked him, “Do you want me to come sit with you, and do you want me to guide you through this?”

He motioned with his hand, inviting me to sit close by on the bed. He took the oxygen mask off himself.

I said, “Allow yourself to be fully aware of your breathing, and follow your in-breath and your out-breath. Just in between the in and out-breath there is a still point where there is only stillness, before the in-breath starts again. Can you feel that? Gradually, allow your out-breath to become a little bit longer, and just relax into that. Is that okay for you?”

He laid his hand very gently down next to mine, not grasping. He looked at me as if to say, “I got it, I don’t have to hold on any more.” In a few breaths he relaxed completely and his breathing stopped.

It is so touching to witness this letting go, fully conscious and without resistance. He was a great teacher. That was a gift.

Barbara: Where do you see the direction of your work continuing?

Rochelle: I see myself as a privileged listener and I go where I am invited. My hope, my vision, is that my story will be an inspiration for other people to develop their own ways of healing into their own life and death. I’ve trained a few people to continue working with the emotions as I learned from Elisabeth. I’ve done this work throughout Europe, and also in Israel and the USA. At present there are fewer people dying from AIDS, so our center in Holland has become more of a mindfulness practice center for anyone interested in exploring their own answers around loss and change.

In addition to this work in Holland, we have opened a center in Spain where I’ve also been working for the last ten years and there is a team trained to offer similar work there. The last couple of years I’ve been invited to Israel several times, and with the situation in the Mideast right now, I think there’s an awful lot of work to do there. And there’s the AIDS crisis in Africa, Central and South America, and Asia. Some of the newer pain medications have become available in Vietnam for people with cancer; however this medication and nearly all medical care, is denied the people dying of AIDS. I do not have the illusion that I am going to all of those places, but there is much to be done. I’m watching to see what doors open as I continue being a privileged listener and training others to be also.

What I’ve learned very deeply because I’ve been so ill, is we have to take the time to take care of ourselves. We can’t care for anybody else until we take care of ourselves. At present I’m in a new phase of finding my personal balance between doing and not doing.

Barbara: Do you live in chronic pain still?

Rochelle: I have some pain always, in varying degrees, depending on how well I’ve been able to keep myself in balance. I use a combination of some medication, but mostly I use what I call my M.M.&M. therapy (meditation, massage and manual therapy) as well as taking care of my emotional needs and making time for myself to just gaze at the frogs in the pond. Every time someone dies or leaves, I feel the grief very physically. I recognize my grief when my heart feels closed off and often I feel physically cold and uncomfortable. What I’ve found is that I move through the grief process when I’m willing to go deeply into my feelings, including the resistance, by letting myself cry, feel anger, and whatever else I need to do. I am becoming more skillful at embracing these feelings without needing to express them fully; just recognizing them and their original source is often enough. Then my heart can open, be free, and feel supported by the love in the universe again. That’s what I think has helped me to repeatedly regain my balance, along with the support of my Sangha and my partner, throughout the eighteen years that I’ve worked so intensively in this field.

Barbara: As the process of birth has been brought out of the closet, you are helping to bring the process of dying into awareness also. We all need work like yours to help us to face death.

Rochelle:Yes. I’ve offered many trainings for volunteers and for healthcare professionals in the field of palliative care, and the work is always about our own issues. We often think, as professionals, we come into this work because we want to help others, but we have to help ourselves first. Because in dealing with dying people, if you aren’t completely authentic, they know! They are always a few steps ahead of us showing us the way!

Barbara: It’s like being with children.

Rochelle: Absolutely. You can’t fool them at all. They know when you’re being real and when you’re not!

Barbara: [laughs] That’s true! Well, thank you so much for sharing your story with the worldwide Sangha.

Rochelle: Thank you for asking.

Rochelle Griffin, True Light of Peace, Chân An Quang, practices with the Sangha Riverland. She lives with her partner, Jantien, and their golden retriever, ‘Gino-the-Joyful’ at the Vuurvlinder Center and Guesthouse for conscious living and dying, in Heerewaarden, a small village in the center of The Netherlands. Rochelle enjoys learning about the wild environmental needs of reptiles by breeding them in the safety of her large garden.

Barbara Casey, True Spiritual Communication, is the managing editor of the Mindfulness Bell.

Photos by Harry Pelgrim.