By Alexa Singer-Telles

Like many Sanghas, we hold days of mindfulness in members’ homes to enjoy the traditional practices of mindful breathing, sitting, walking, and eating. Our days together were enriched early on as we began to experiment with bringing other creative activities into our days of mindfulness. These opportunities grew organically by inviting our Sangha members to share the fruits of their talents. Not only did we experience a variety of gardens to walk in,

By Alexa Singer-Telles

Like many Sanghas, we hold days of mindfulness in members’ homes to enjoy the traditional practices of mindful breathing, sitting, walking, and eating. Our days together were enriched early on as we began to experiment with bringing other creative activities into our days of mindfulness. These opportunities grew organically by inviting our Sangha members to share the fruits of their talents. Not only did we experience a variety of gardens to walk in, but we varied our mindful movements, celebrated rituals for special occasions, and experimented with art.

In a recent conversation with an Order of Interbeing member about creativity and practice, it was mentioned that Thay wrote that though there are 84,000 Dharma doors, we are given the task to invent new doors for our contemporary needs. This was an important reminder to me not to get stuck in the view that there is a rigid form, but rather to allow the form to be the fertile ground where mindfulness can grow in many ways. This invitation for creativity and bringing our gifts into the practice parallels my experience with Jewish Renewal, a recent movement in Judaism. In their philosophy, Jews who left the tradition to explore other spiritual paths are welcomed back into Judaism. This inclusiveness is contrary to other approaches which insist that you leave other ideas at the door; instead it encourages these returnees to weave the teachings and gifts they have received from other spiritual traditions into their practice. The phrase coined to describe these spiritual explorers is “hyphens,” to honor their eclectic heritage. Rather than preserving the purity of a religious tradition, this invitation allows a rich interweaving of experience to inform spiritual practice and hopefully deepen it. In this modern time, where many of us have come to Buddhism from another root religion and have explored other spiritual paths, it is inevitable that we come to this practice made up of non-Buddhist elements. Welcoming in these valuable elements honors the wisdom of our experience and enriches the life of our Sangha.

One of the first opportunities for creative practice came when Rod, an artist in the Sangha, invited us to his home studio for a day of mindfulness. We sat in the warm spring sun on the deck and enjoyed sitting meditation and some body awareness exercises. Then we were each given a small ball of clay and invited to be present to its shaping. He explained the Japanese aesthetic, wabi sabi, “a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.” He guided us in this unpretentious and simple approach, by encouraging the natural process to unfold. Our task was to breathe mindfully and feel the experience of molding clay into a small cup. Our eyes were closed to feel the sensations of form developing through our fingers.

Afterwards we placed the cups in the center of the circle to admire the uniqueness of each cup and share our experiences and insight. The next week, Rod brought our glazed cups to our weekly sit. They had transformed from plain gray clay into multi-colored, crackled raku cups. My cup sits on my altar to this day, a piece of imperfect art, pleasant to the eye, and holding memories from a wonderful day.

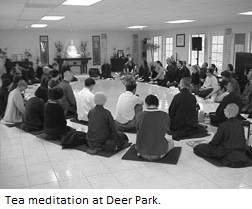

The pleasure our Sangha members derived from this art-making encouraged us to continue to offer creative expression to our group. Recently, one of our members volunteered to lead us in a Japanese tea ceremony during a day of mindfulness. Sandra had studied tea ceremony and was eager to share this special practice with us. The tea ceremony became the centerpiece of our day, and when our planning committee gathered, we had fun brainstorming ideas to enhance the experience of the tea ceremony. We designed a Japanese-style altar with such items as a parasol, a fan, a Buddha, and an ikebana flower arrangement. On the day of mindfulness, to our delight, one member brought a bonsai maple tree for the altar. These pieces made an interesting yet serene focal point for the room. To me the creation of an altar is like making an offering to the Buddha as well as giving a gift to the entire Sangha.

We usually include mindful movements as a way to remember to care for our bodies. At times we have added yoga stretching, body awareness exercises, and four elements breathing and movements from Sufi tradition. On this day our movement form was chi gong exercises in keeping with our Asian theme.

At the conclusion of our days together, we often share poetry, songs, and reflections. For this special Day of Tea, I suggested that everyone be invited to write a haiku (short poem) as a way to translate our awareness and experience into art. To give some background and preparation for haiku writing, I offered a brief teaching from the Japanese poet, Basho, one of the greatest contributors to the development and art of haiku. Basho’s teachings are very much in alignment with the practice of mindfulness and interbeing. His teachings guide the writer into an awareness of our deep connection with the natural world. He suggests that by immersing oneself in the impersonal life of nature, one can resolve deep dilemmas and attain perfect spiritual serenity (sabi). He found that the momentary identification of man with inanimate nature was also essential to the poetic creation(1). Connecting with the natural world, especially during mindful practice, has brought me a direct experience of peace and tranquility many times. It was my hope that this exercise would be an opportunity for Sangha friends to experience this Dharma door of awareness.

The day was wonderful. The tea ceremony brought us into the serene beauty of the tradition and formality of drinking tea. We were given a bit of tea history and strict instructions, including how to pass the bowl, when to admire its beautiful hand-painted designs, and how many gulps to drink. One at a time, we were passed the freshly made bowl of tea, drinking it in three gulps, admiring the floral design of the bowl, and passing the cup back to the server. We listened silently to the stirring, passing, and gulping of the tea as it went around the circle. The tranquility of tea was palpable. My haiku expressed my sense of being transported back into the stream of ancestral tea drinkers.

Green tea stirs my heart,

The ancient ones whispering

Enjoy every drop!

A growing sense of awareness of our presence and interconnectedness with the natural world seemed to be captured in the haikus that were written that day. The poems, like our cups crafted many years ago, are tangible evidence of our experiences. They embody the sense of clarity that grows when we take the time to share a day of mindfulness. Here are some examples.

Hands stretch to heaven

The sun is not far away

Feet sink through the earth.

-Greg White, Mindful Clarity of the Heart

Damp concrete walkway

Urges my bubbling sole

To know its cool kiss

-Christine Singer

Six shoes in a row

Where are the master’s feet now

Joyful in the grass

-Sandra Relyea

Hot water pouring

The cup of tea goes around

Gulping the tea is magic

-Susane Grabiel

Butterfly on stone

Wings opening and closing

She’s breathing the sky

-Terry Helbick, True Original Land

As I reflect on this particular day of mindfulness through these poems, it is clear to me that the most important ingredient for a day of practice is the sincere presence and -willing participation of the Sangha members. The gifts of awareness that grow in us can be so beautifully expressed in art-making and other creative forms. Simply by welcoming and weaving into our practice the talents of our Sangha friends, the possibilities for creating beauty in mindfulness abound.

Alexa Singer-Telles, Steady Friend of the Heart, is a member of the River Oak Sangha in Redding, California. A psychotherapist and artist, she is an aspirant to the Order of Interbeing.

- Ueda, Makoto, The Master Haiku Poet: Matsuo Basho. (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1982