by Christine Dawkins

During the Vietnam War, Thich Nhat Hanh and the young members of the School of Youth for Social Service braved the mine-laden fields of the embattled countryside to bring food, clothing, building materials and medical supplies to the villagers whose homes and families had been destroyed. Later, Thay wrote in Lotus in a Sea of Fire that all that is beautiful contains suffering, and that all suffering can bring forth great beauty.

by Christine Dawkins

During the Vietnam War, Thich Nhat Hanh and the young members of the School of Youth for Social Service braved the mine-laden fields of the embattled countryside to bring food, clothing, building materials and medical supplies to the villagers whose homes and families had been destroyed. Later, Thay wrote in Lotus in a Sea of Fire that all that is beautiful contains suffering, and that all suffering can bring forth great beauty. The sea of fire that was the war in Vietnam brought forth the lotus of Plum Village, its sister monasteries in the United States, and the many practice centers and Sanghas that have grown all over the globe. It has also brought the Vietnamese and Western worlds together into a family that is beautiful and diverse.

My guilt, grief, and anger towards my government have been held in the arms of the forgiveness, faith, and resilience with which the Vietnamese people I met have embraced their lives. I can only hope my listening to their stories also brought them a small measure of the peace and healing they brought to me.

On January 27, 1972, the Paris Peace Accords were signed, ending the ten-year presence of the United States military in Vietnam and giving the U.S. sixty days to withdraw all troops and dismantle all military bases within South Vietnam. For most Americans, this ended the long and futile nightmare of a costly war. While there would be many social, political, and economic consequences, most of us in the U.S. breathed a sigh of relief and tried to put the war behind us.

Although the Paris Peace Accords provided for the reunification of Vietnam, it was common knowledge that the invasion of South Vietnam by Viet Cong military forces was now inevitable. The accords also provided that the unification was to be accomplished without foreign interference. But although the United States had withdrawn its support of South Vietnam, the North Vietnamese still received support and arms from Russia and China. No longer fettered by U.S. presence in the South, and in direct violation of the accords, Communist soldiers marched southward through the devastated countryside, occupying town after town, until they reached their final destination, Saigon.

Saigon fell on April 30, 1975. Aware that their days of freedom were numbered, thousands of South Vietnamese attempted to flee the country in the weeks prior to the fall, but only a lucky few had the connections to obtain exit visas. Life under the Communists was intolerable for many, especially high-ranking South Vietnamese military officials. I met one man who had been told that he just needed to go to a few classes explaining the new regime’s rules, but ended up in a reeducation camp for five years. These so-called camps were really prisons, where the inmates were forced to perform hard labor under inhumane conditions.

Thus were the Boat People born, hundreds of thousands of courageous men, women, and children who entrusted themselves to the China Sea in the hope of finding a better future for themselves and their children. In 1986, it was estimated that one million Vietnamese refugees had taken to the China Sea in small boats. Many of these people relocated to the United States, Australia, Canada, France, and other European countries. There is no way to know how many never made it. Some believe another million died on the way by drowning, starvation, dehydration, or at the hands of Thai pirates who routinely attacked, robbed, tortured, abducted, raped, sold into prostitution, or murdered the refugees.

The Boat People began their exodus in 1975. By 1979, the number of people braving the China Sea had mounted significantly. Unfortunately, so did the number of pirates. These pirates were Thai fishermen who had learned that piracy was more lucrative than fishing. Because the Vietnamese had been forced to leave everything behind, many of them sold whatever they could to bring gold for their new start in life. In small boats that easily capsized, filled way beyond their capacity with passengers with little or no seafaring skills, the boat people were easy prey for the pirates.

Just getting a space on a boat was no small task. Vietnam was even more divided after the war than during it. Sometimes there were Communists and freedom fighters in the same family. Under the Communist regime, it was very important to keep up the appearance of a humble hard-working Communist. This meant knowing who could be safely approached to arrange for escape.

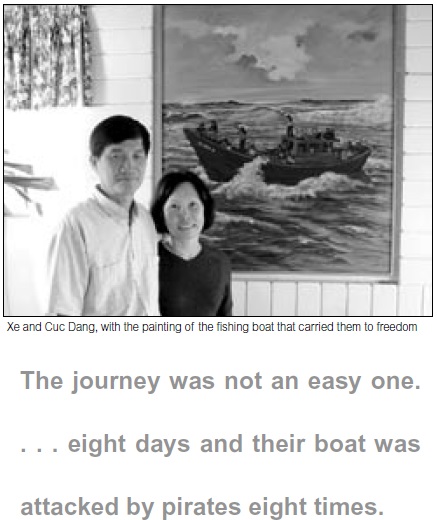

One couple, Cuc and Xe Dang, made several attempts before they managed to get on a boat. During one attempt, the family had to split up. Xe went with one group while Cuc was scheduled to take off with another. It was nighttime and the group Xe was going with was being ferried out to the fishing boat in a small rowboat. Xe insisted on going last, as three years in a re-education camp had taught him to listen to his instincts. Half the group had already been ferried out when the Communist police captured the escapees. Xe was able to intercept his wife and then had to hide for several months, having already been singled out by the Communists for the harsher treatment given to those who had worked for the Americans.

In the meantime, Cuc’s father was approached by someone who asked if his son-in-law might be interested in going in a boat with him and some others. This is the boat that finally carried them to freedom. The journey was not an easy one. They had a one-year old and a four-year-old child and traveled with some young nieces and nephews. During the eight-day trip, their boat was attacked by pirates eight times.

The first time, the pirates took everything, including food, clothes, watches, and jewelry. Even their spare engine was stolen. They were made to strip and were searched. Other times they were left alone when the pirates saw they had nothing. But one time, the pirates took three young women onto their boat and raped them. “We were very scared,” Cuc said, “and thought we would be next. But then a friend, who knew a little English said, “Pray to Buddha.’” Cuc laughed, “I did not know who Buddha was. But I prayed with the others out loud. ‘Please, Buddha, help us, Buddha! Please help us, Buddha!’ over and over again. It turned out the pirates were Buddhist and they got scared when they heard us calling Buddha, so they left!” Cuc asked her friend, “Who is this Buddha we called to?” “It is But!” her friend answered. “I had no idea that Buddha was the English word for But. I thought I was praying to some strange God.,” Cuc said.

But their difficulties were not over. When they finally made it to Malaysia, they were told the refugee camp could not accept them. They stayed on shore during heavy rains in a place without a roof and only a pit dug into the ground for a toilet.

After several days, an official told them they were going to be taken somewhere in preparation of being sent to the United States. They were told to get into their boats, which were tied in a chain and attached to a Malaysian ship. Cuc and Xe’s boat was the last boat of eight. The ship took to sea, going too rapidly for the small fishing boats to withstand the ocean waves that poured in from the ship’s wake. Xe told the others in his boat, “We are going to sink unless we untie ourselves.”

It had become apparent their destination was not the United States, but the middle of the ocean. The boats were being watched by the Malaysian officials on the ship’s deck, but since it was dark and Xe’s boat was last in line, someone was able to crawl out to the prow and cut the line. Solemnly, they watched as the other boats were towed helplessly out to the open ocean, their hulls filling with water.

One of the first things Cuc did when she finally made it to the United States was commission a painting depicting the boat that carried Cuc, her husband and two children over the turbulent China Sea from Vietnam to freedom. “When we finally arrived in the United States, we had lost everything,” Cuc recalls. She glances over at the large oil painting above her fireplace. “The painting, done by a famous Vietnamese artist, was very expensive. But I did not care about the cost.” In the painting, the small fishing boat bobbing precariously in the foaming waves is emblazoned with the number of the boat they escaped on. “I bought it so we would never forget our escape, so that my children will always know: We are Boat People! When they do poorly at school, when some difficulty comes up for us, we stand in front of this painting, and I remind them. We are Boat People!”

Christine Dawkins, True Wonderful Mind, practices with her daughters, Siena and Chiara, at Deer Park, with the Still Water Sangha in Santa Barbara.