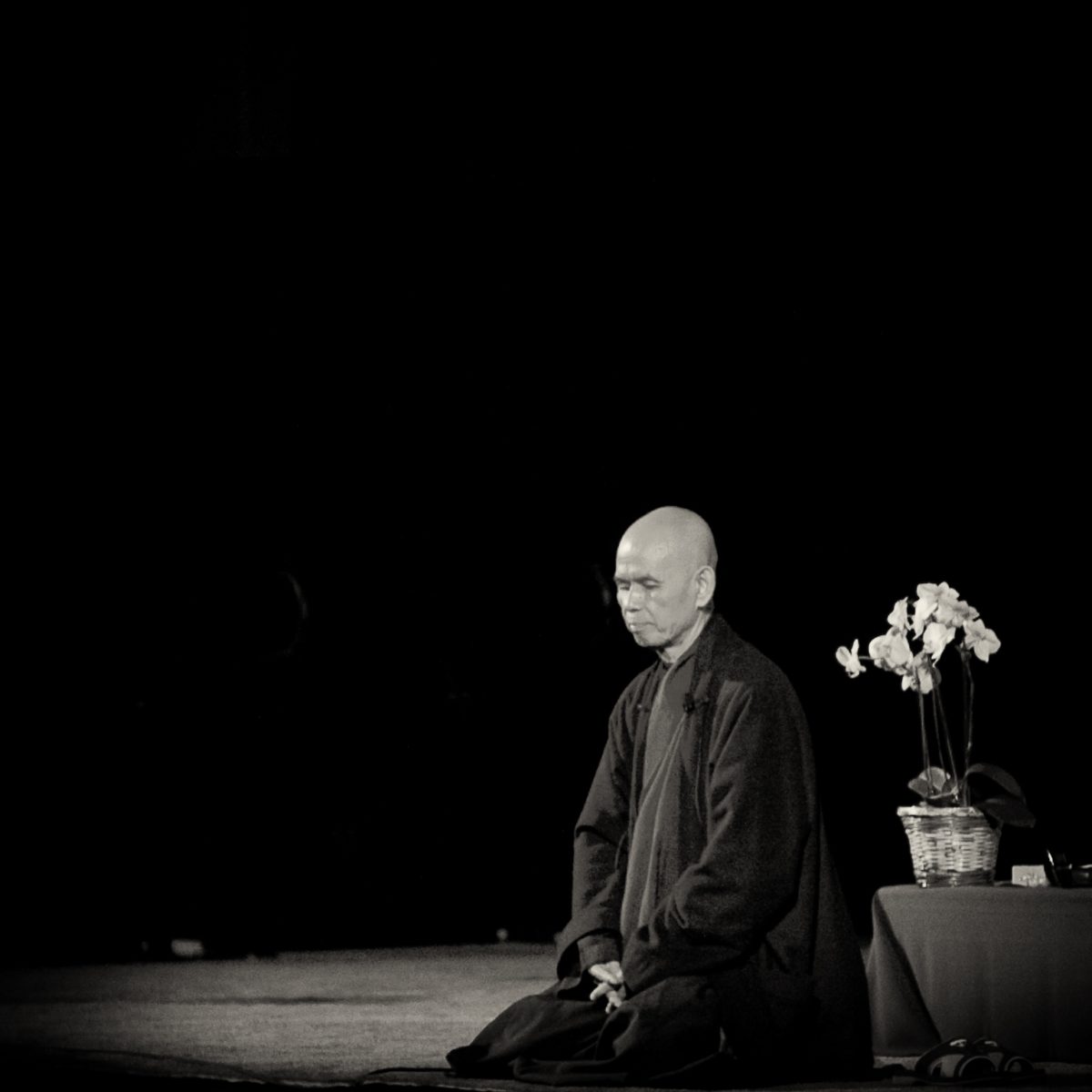

Dharma Talk at Stonehill College, Massachusetts

August 16, 2009

Today is the last day of our five-day retreat. We will speak about the sixteen exercises proposed by the Buddha on mindful breathing.

The first four exercises are about practicing with the body. The second set of four are practicing with feelings. The third set of four are practicing with the mind.

Dharma Talk at Stonehill College, Massachusetts

August 16, 2009

Today is the last day of our five-day retreat. We will speak about the sixteen exercises proposed by the Buddha on mindful breathing.

The first four exercises are about practicing with the body. The second set of four are practicing with feelings. The third set of four are practicing with the mind. And the last four are about practicing with the objects of mind.

Body-Centered Practice

The first exercise is to identify the in-breath and out-breath. Breathing in, I know this is my in-breath. Breathing out, I know this is my out-breath. To recognize my in-breath as in-breath.

The second is to follow my in-breath all the way through. By doing so, I keep my mindfulness and concentration strong. I preserve my mindfulness and concentration during the whole time of my in-breath and my out-breath.

The third exercise is: Breathing in, I am aware of my whole body. This exercise will bring mind and body together. With mind and body together, we are truly established in the here and the now, and we can live our life deeply in each moment.

The fourth exercise is to release tension in our body. These four exercises help the body to be peaceful. They help us to take care of our body.

Practicing with Feelings

With the fifth exercise we come to the realm of feelings. We bring in a feeling of joy. We cultivate and recognize joy within us.

With the sixth exercise we bring in happiness. The practitioner knows that mindfulness is a source of happiness. Mindfulness helps us to recognize the many conditions of happiness we already have. So to bring in a feeling of joy, to bring in a feeling of happiness, is easy. You can do it any time.

There is a little difference between joy and happiness. In joy there is still some excitement. But in happiness you are calmer. In the Buddhist literature there is the image of someone very thirsty walking in the desert, and suddenly he sees an oasis, trees encircling a pond. So he experiences joy. He has not drunk the water yet. He is still thirsty, but he is joyful because he needs only to walk a few more minutes to arrive at the pond. That is joy. There is some excitement and hope in him. And when that traveler comes to the oasis, kneels down and cups his hands, and drinks the water, he feels the happiness of drinking water, quenching his thirst. That is happiness, very fulfilling.

The practitioner should be able to make use of mindfulness, concentration, in order to bring himself or herself a feeling of joy, a feeling of happiness, for his own nourishment and healing. Just with mindful breathing, mindful walking, we can bring in moments of happiness and joy, because the conditions of happiness are already sufficient inside of you and around you.

The seventh exercise is to be aware of painful feelings. When a painful feeling or emotion manifests, the practitioner should be able to be present in order to take care of it. With mindfulness, she will know how to recognize and embrace the pain, the sorrow, to get relief. She can go further with other exercises in order to transform, but now she’s only recognizing and embracing. Recognizing and embracing tenderly the feeling of pain and sorrow can already bring relief.

The eighth exercise is to release the tension, to calm the feeling. So the second set of four exercises is to deal with feelings. The practitioner should know how to recognize her feelings, and know how to embrace and deal with her feelings, whether they are pleasant or unpleasant.

Practicing with Other Mental Formations

With the ninth exercise, we come to the other mental formations. Feeling is just one category of mental formations. In Buddhist psychology we speak of fifty-one categories of mental formations. Formation—samskara—is a technical term. This pen [Thay holds up a pen] is a formation, because many conditions have come together in order for it to manifest as a pen. It is a physical formation. My hand is a formation, a physiological formation. My anger is a formation, a mental formation. We have fifty-one categories of mental formations, the good ones and the not-so-good ones.

The ninth exercise is to become aware of any mental formation that has manifested. There is a river of consciousness that’s flowing day and night. Anger, hate, despair, joy, jealousy, compassion, all continue to take turns manifesting. As a practitioner, you are always present so you can recognize them. You don’t need to fight or to grasp; you just recognize them as they arise, as they stay for some time, and as they go away. There is a river of mind in which every mental formation is a drop of water, and you observe the manifestation and the going away of that mental formation. Don’t try to grasp, don’t try to fight. Just calmly recognize them, smile to them, whether they are pleasant ones or unpleasant ones.

The tenth exercise is to gladden the mind, to make the mind glad, to bring vigor to the mind. There are so many good seeds in us, like the seed of mindfulness, the seed of concentration, the seed of insight, the seed of joy, the seed of peace. We should know how to touch the seeds in our store consciousness, and how to invite them to come up. Then the landscape becomes very pleasant.

It’s as if you have some films on DVDs, and many are very uplifting. As a practitioner, you know how to select a movie that will bring joy and happiness. Suppose you are watching a film that contains violence, hate, and fear. You know that it is not good for you to watch, but you don’t have the courage to turn it off, because you feel that if you turn it off, then you will have to confront the fear, the anger, the loneliness inside you. You are using the film to cover up your afflictions.

The Buddha advises us that there are many good DVDs available, and you have to choose good DVDs in order to watch the fine films that are available. The DVDs of Buddhahood, of understanding, compassion, forgiveness, joy, and peace are always there. So to select DVDs that can bring joy, encouragement, strength, aspiration, compassion, is the object of the tenth exercise. We can practice that together. We can help another person to touch the good things in her, so that she will have the energy and strength to succeed in her practice.

The eleventh exercise proposed by the Buddha is to bring the mind into concentration. The Buddha has proposed many topics of concentration for us to use, to concentrate the mind.

The twelfth exercise is to liberate the mind. The mind is tied up, caught by the afflictions of sorrow, of fear, of anger, of discrimination. That is why we need the sword of concentration in order to cut away all these binding forces.

Impermanence: Notion or Insight?

Suppose we speak about the concentration on impermanence. We have a notion of impermanence and we are ready to accept that things are impermanent. You are impermanent, I am impermanent. But that notion of impermanence does not help us, because although you know intellectually that your beloved one is impermanent, you believe she will be here for a long time, and that she will be always the same. Everything is changing every moment, like a river, and yet you still think of her as she was twenty years ago. If you are unable to touch her in the present moment, you are not in touch with the truth of impermanence.

Using mind consciousness, you need to meditate to touch the true nature of impermanence. You need the concentration, the insight of impermanence rather than the notion of impermanence to liberate you.

The notion of impermanence may be an instrument which can help bring about an insight into impermanence. In the same way, a match is not a flame, but a match can bring about a flame. When you have the flame, it will consume the match. What you need is the flame and not the match. What you need for your liberation is the insight of impermanence and not the notion of impermanence. But in the beginning the notion, the teaching of impermanence can help to bring the insight of impermanence. When the insight of impermanence is there, it burns up the notion of impermanence.

Most of us get caught in notions when we learn Buddhism. We don’t know how to make skillful use of these teachings in order to bring about insight. We have to practice. While sitting, walking, reading, drinking, we are concentrating on the nature of impermanence. That is the only way to touch the insight of impermanence. Concentration means to keep that awareness alive, moment after moment, to maintain it for a long time. Only concentration can bring insight and liberate you.

Suppose you and your husband disagree about something. You are angry and are about to have a fight. Suffering is in you, suffering is in him, and the mind is not free. To free yourselves from anger, you need concentration. Let us try the concentration on impermanence. You close your eyes. “Breathing in, I visualize my beloved one 300 years from now. What will he become in 300 years? What will I become in 300 years?” You can touch the reality of impermanence. “We have a limited time together, and we are wasting it with our anger, with our discrimination. That’s not very intelligent.”

When you visualize both of you 300 years from now, you touch the nature of impermanence and you see how unwise you are to hold on to your anger. It may take only one in-breath or one out-breath to touch the nature of impermanence in you and in him. With that insight of impermanence you are free from your anger. “Breathing in, I know I am still alive and he is still alive.” When you open your eyes, the only thing you want to do is to take him into your arms.

That is liberating with the insight of impermanence. If you are inhabited by the insight of impermanence, you will deal with him or with her very wisely. Whatever you can do to make him happy today, you do it. You don’t wait for tomorrow, because tomorrow may be too late. There are those who cry so much, who beat their chests, who throw themselves on the floor when the other person dies. That is because they remember that when the other person was alive, they did not treat him or her well; and it is the complex of guilt in them that causes them to suffer. They did not have the insight of impermanence.

Impermanence is one concentration. In Buddhism, impermanence is not a doctrine, a theory, a notion. It is an instrument, it is a concentration, a samadhi. The Buddha proposed many concentrations; for example, the concentration on no-self. When the father looks into his son and sees himself in his son, his son is his continuation. His son is not a separate person. So he can see the nature of no-self in him and in his son. He sees that the suffering of his son is his own suffering. When he sees that, he is free from his anger.

Investigating Objects of Mind

In Buddhism the world is considered the object of mind. Our mind, our consciousness, our perception, may be described as having two components: the knower and the knowable. In Buddhism when you write the word “Dharma” with a capital letter, it means the teaching, the law. When you write the word “dharma” with a small letter, it means the object of your mind. The pen is the object of my mind. The flower is the object of my mind. The mountain, the river, the sky are the objects of my mind. They are not objective reality; they are objects of my mind.

The last four exercises investigate the nature of the objects of our mind. Many scientists are still caught in the notion that there is a consciousness in here, and there is an objective world out there. That is the most difficult obstacle for a scientist to overcome.

In Buddhism we call it “double grasping,” when you believe that there is a consciousness inside, trying to reach out, to understand the objective world out there. Buddhism explains that subject and object cannot exist separately, like the left and the right. You cannot imagine the existence of the left without the right.

Consciousness is made of the knower and the knowable. These two manifest at the same time. It’s like up and down, left and right. An object of mind is the business of perception. You perceive something, whether that something is a pen, or a flower. The object of perception always manifests at the same time as the subject of perception. To be conscious is always to be conscious of something. To be mindful is to be mindful of something. You cannot be mindful of nothing. To think is to think about something. So the object and the subject manifest at the same time, like the above and the below, the left and the right. If you don’t see it like that, you are still caught in double grasping.

The thirteenth exercise is contemplating impermanence. Impermanence is just one concentration. But if you do it well, you also succeed in the contemplation of no-self, because going deeply into impermanence, we discover no-self. We discover emptiness, we discover interbeing. So impermanence represents all concentrations.

While breathing in, you keep your concentration on impermanence alive. And while breathing out, you keep your concentration on impermanence alive, until you make a breakthrough into the heart of reality. The object of your observation may be a cloud, a pebble, a flower, a person you love, a person you hate, it may be your self, it may be your pain, your sorrow. Anything can serve as the object of our meditation.

Contemplating Non-Desire

The fourteenth exercise is contemplating non-desire, noncraving. It has to do with manas, that level of our consciousness that always runs toward pleasure. If you look deeply into the object of your craving, you will see it’s not worth running after. Instead, being in the present moment, you can be truly happy and safe with all the conditions of happiness that are already available. Because manas ignores the dangers of pleasure-seeking, this exercise is to help manas to enlighten, to see that pleasure-seeking is dangerous and you risk damaging your body and your mind. If you know how to be in the present moment, happiness can be obtained right away.

No Birth, No Death

The fifteenth exercise is contemplating nirvana. This is real concentration. This concentration can help us touch the deep wisdom, the nature of reality that will be able to liberate us from fear and anger and despair.

In Buddhism the word nirvana means extinction. Nirvana is not a place you can go. Nirvana is not in the future. Nirvana is the nature of reality as it is. Nirvana is available in the here and the now. You are in nirvana. It’s like a wave arising on the surface of the ocean. A wave is made of water, but sometimes she forgets. A wave is supposed to have a beginning, an end. A coming up, a going down. A wave can be higher or lower than other waves, more beautiful or less beautiful than other waves. And if the wave is caught by these notions—beginning, ending, coming up, going down, more or less beautiful—she will suffer a lot.

But if the wave realizes she is water, she enjoys going up, and she enjoys going down. She enjoys being this wave, and she enjoys being the other wave. No discrimination, no fear at all. And she doesn’t have to go and look for water; she is water in the present moment.

Our true nature is the nature of no beginning, no end, no birth, no death. If we know how to touch our true nature of no birth and no death, there is no fear. There is no anger, there is no despair. Because our true nature is the nature of nirvana. We have been nirvanas from the non-beginning.

The other day we talked to the children about a cloud. We said it’s impossible for a cloud to die, because in our mind, to die means from something you suddenly become nothing. From someone you suddenly become no one. And grief is the outcome of that kind of outlook. It is possible for a cloud to become rain or snow or hail, or river, or tea, or juice. But it is impossible for the cloud to die. The true nature of the cloud is the nature of no death.

So if you have someone close to you who just passed away, be sure to look for her or him in her new manifestation. It’s impossible for her to die. She is continued in many ways, and with the eyes of the Buddha you can recognize him, you can recognize her, around you and inside of you. And you can continue to talk to him, talk to her. “Darling, I know you are still there in your new forms. It’s impossible for you to die.”

The nature of the cloud is also the nature of no birth. To be born, in our mind, means from nothing you suddenly become something. From no one you suddenly become someone. That is why you need a birth certificate. We seem to believe that from non-being we have passed into being. And when we die, from being we pass into non-being again. That is our way of thinking, which is erroneous. Before becoming a cloud, the cloud has been the ocean water, the heat generated from the sun. The cloud has not come from nothing. Her nature is the nature of no birth and no death. So this meditation helps us to remove all notions, including the notions of beginning, ending, being, and non-being.

Suppose I draw a line representing the flow of time, from left to right. And I pick up one point as the point of birth. They say that I was born on that moment, “B”. It means that the segment before “B” is characterized by my non-being. No being. And suddenly from point “B” I begin to be. And I might last, maybe 120 years [laughter], and suddenly I will come to the point “D”. And from being I pass into non-being again. That is the way we think. We think in terms of being and non-being.

To the children we said that before the date of their birth, they already existed in the womb of their mother. They spent about nine months in the womb of their mother. So it’s not true to say that they began to exist on the day of their birth. The birth certificate is not correct. But did you begin to exist at the moment of conception? Before your conception, you already existed at least half in your father and half in your mother. You have not come from nothing, from non-being. You have always been there in one form or another. So your nature is the nature of no birth.

Extinction, nirvana, means the extinction of all notions, including the notion of birth and death, the notion of being and non-being. We remove all views, all notions. That is the job of the fifteenth exercise.

There are theologians who say that God is the ground of being. But if God is the ground of being, who will be the ground of nonbeing? God transcends both notions of being and non-being. The fifteenth exercise is to remove, to transcend all kinds of notions. True happiness, non-fear, is possible only when all these notions are removed.

Imagine our beautiful wave. She now recognizes that she is water, and knowing that she is water she is no longer afraid of beginning, ending, coming up, going down. She enjoys every moment. She doesn’t have to go and look for water; she is water. Our true nature is the nature of no birth and no death, no being and no non-being.

The sixteenth exercise is to throw away, to release all these notions, and to be completely free.

The Sutra on Mindful Breathing offers sixteen exercises on mindful breathing that cover four areas of life: body, feelings, mind, and objects of mind. We can use the sutra as a manual to practice meditation. Together with the sutra called the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, the Sutra on Mindful Breathing is very precious. A real gift from the Buddha. In the Plum Village Chanting Book, you can read both the Sutra on Mindful Breathing and the Sutra on the Four Establishments of Mindfulness, which are common in every school of Buddhism.

Dear friends, as I told the children, the Sangha is always there. It is a joy when you see the Sangha manifesting like this. Please continue with your practice. Please share the practice with your friends and help bring joy and peace and hope to our society. Continue to be a torch. Each of you is a continuation of the Buddha. We should keep the Buddha alive, the Dharma alive, the Sangha alive in every moment of our daily lives.

When you go home, please do your best to set up a group of practitioners in order to have a refuge for many people who live in your area.

Discourse on the Full Awareness of Breathing

“O bhikkhus, the full awareness of breathing, if developed and practiced continuously, will be rewarding and bring great advantages. It will lead to success in practicing the Four Establishments of Mindfulness. If the method of the Four Establishments of Mindfulness is developed and practiced continuously, it will lead to success in the practice of the Seven Factors of Awakening. The Seven Factors of Awakening, if developed and practiced continuously, will give rise to understanding and liberation of the mind.

“What is the way to develop and practice continuously the method of Full Awareness of Breathing so that the practice will be rewarding and offer great benefit?

“It is like this, bhikkhus: the practitioner goes into the forest or to the foot of a tree, or to any deserted place, sits stably in the lotus position, holding his or her body quite straight, and practices like this: ‘Breathing in, I know I am breathing in. Breathing out, I know I am breathing out.’

- ‘Breathing in a long breath, I know I am breathing in a long breath. Breathing out a long breath, I know I am breathing out a long breath.

- ‘Breathing in a short breath, I know I am breathing in a short breath. Breathing out a short breath, I know I am breathing out a short breath.

- ‘Breathing in, I am aware of my whole body. Breathing out, I am aware of my whole body.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I calm my whole body. Breathing out, I calm my whole body.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I feel joyful. Breathing out, I feel joyful.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I feel happy. Breathing out, I feel happy.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I am aware of my mental formations. Breathing out, I am aware of my mental formations.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I calm my mental formations. Breathing out, I calm my mental formations.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I am aware of my mind. Breathing out, I am aware of my mind.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I make my mind happy. Breathing out, I make my mind happy.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I concentrate my mind. Breathing out, I concentrate my mind.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I liberate my mind. Breathing out, I liberate my mind.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I observe the impermanent nature of all dharmas. Breathing out, I observe the impermanent nature of all dharmas.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I observe the disappearance of desire. Breathing out, I observe the disappearance of desire.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I observe the no-birth, no-death nature of all phenomena. Breathing out, I observe the no-birth, no-death nature of all phenomena.’ He or she practices like this.

- ‘Breathing in, I observe letting go. Breathing out, I observe letting go.’ He or she practices like this.

“The Full Awareness of Breathing, if developed and practiced continuously according to these instructions, will be rewarding and of great benefit.”

Excerpted from “Discourse on the Full Awareness of Breathing,” Plum Village Chanting and Recitation Book, compiled by Thich Nhat Hanh and the Monks and Nuns of Plum Village, Parallax Press.

To request permission to reprint this article, either online or in print, contact the Mindfulness Bell at editor@mindfulnessbell.org.