By Brother Chan Phap Lai

Thay’s offering, Bat Nha: A Koan, is intended to nourish our collective bodhicitta—the mind of love. Thay has contributed his deep insight and invites us all to read, contemplate and practice in order to come to our own insight—the kind of insight that can show a way out.

The situation, as it has developed,

By Brother Chan Phap Lai

Thay’s offering, Bat Nha: A Koan, is intended to nourish our collective bodhicitta—the mind of love. Thay has contributed his deep insight and invites us all to read, contemplate and practice in order to come to our own insight—the kind of insight that can show a way out.

The situation, as it has developed, is certainly sad in many ways. The Vietnamese Communist Party’s aggressive policy remains steadfast. We continue to pursue our request of France to allow some of the brothers and sisters to take refuge in Plum Village. Still, there is a greater happiness to celebrate. From a spiritual point of view, Bat Nha is a huge success. Here, I want to share a few anecdotes that for me personally gave a more intimate connection to this success.

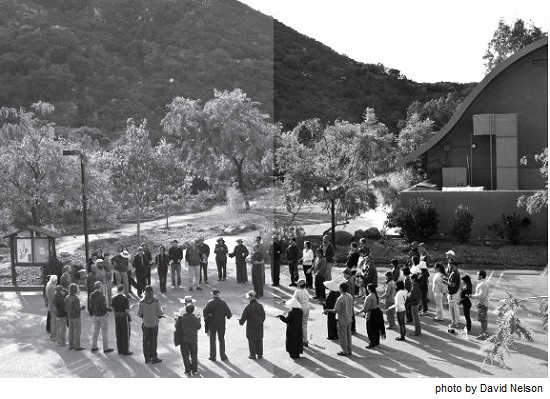

Recently, a number of Most Venerable monks and nuns from Vietnam were able to come to Plum Village and, along with Thay, preside over our annual ordination ceremonies. Some stayed after the week of ceremonies and shared about their monastic life in Vietnam. I asked Ven. Minh Nghia if he would mind my writing articles about his involvement with our Sangha. I understood the Venerables were likely to be given some trouble on their return from Plum Village. Although Ven. Minh Nghia has already been outspoken in his actions to support the Bat Nha Sangha within Vietnam, I wanted to be sensitive. I was most impressed by his response: “You can write what is true—the truth is good.”

There are, of course, many aspects to the truth. One aspect is that the conduct and spirit of the Bat Nha Sangha was admired by the elder monastic community, and they truly wanted to help us. They risked their peaceful coexistence with the government and put their elderly bodies in harm’s way. Ven. Minh Nghia said, “When we saw how bravely the young brothers and sisters were acting, exemplifying the precepts and enduring immense difficulties, we had to act. How could we call ourselves elders of these young monastics if we did nothing but stand by and watch?”

One beautiful aspect of the truth is that the poor townspeople of Bao Loc and neighboring villages loved us. They demonstrated their love in many ways, including secretly bringing food in the middle of the night to the 400 young monastics. This proved a lifeline during the last three months in Bat Nha monastery when electricity and running water had been purposefully cut off. After the forcible eviction from Bat Nha in September, the community took refuge in Phuoc Hue temple in the town of Bao Loc. Here, the government, try as they might, using blackmail, bribes, and relentless propaganda, found it was impossible to enlist locals against the community. Even if the local people could not intercede directly, gaining their respect and love was a spiritual success that made staying in Bat Nha and Phuoc Hue Temple possible and left the local community changed forever.

In an interview concerning the September eviction, Chan Phap Si described how a sister, during a lull in the unpleasantness of the day, handed him a moon cake. (The monastics had, in effect, been starved during the months leading up to the eviction, and were very hungry on the day of eviction.) Phap Si, having noticed a lone policeman standing in the courtyard and knowing the other police had taken time for a lunch break, walked over and offered to share the moon cake. The policeman looked at Phap Si strangely, then politely declined, saying, “You will need it; you have a long journey ahead.” Phap Si was later forcibly driven to his home town and placed under house arrest. In the months that followed, police came around on spot visits to interrogate him. When they came into his house, he skillfully had them partake in a silent tea meditation before answering their questions. As a result, trust developed, and Phap Si found himself listening to the policemen’s personal suffering. They shared their pain concerning the fact that, as police, they often had to do things they felt were wrong.

On the day of eviction from Bat Nha, both Phap Si and Phap Lam placed themselves under a taxi in an effort to prevent their younger brothers from being driven off. They had accepted they were being forced out of their home but were determined not to be dispersed. Phap Lam described his state of mind: “I was not angry with the violent actions of the police and the hired thugs. I was only conscious of my deep love for the brothers.” This desire to protect them led him to place himself under the taxi. His action did not come from an idea to demonstrate non-violently, but was the natural response of a monk who had cultivated no-harm as a way of being, yet wanted to prevent the community from being dispersed.

In Phap Si’s account we heard how a heavy-set policeman tried to drag him away from the taxi wheel he had clasped. The policeman drew back his fist to hit Phap Si. The punch would have been injurious, given the large studded ring Phap Si observed on the policeman’s index finger. At this moment Phap Si said he looked into the eyes of the policeman about to hit him. “I was completely concentrated on compassion, having no fear or resentment, focused only on protecting my younger brothers. I believe the policeman was affected by this because as his fist bore down it seems he lost the heart to follow through and his fist only glanced my face.” Phap Si is convinced it was his concentration on compassion that protected him. “In truth we had nothing and no one to protect us from the ill-will and violence of that day— it was only the energy of compassion generated among us that protected.” There are so many elating anecdotes like this—small triumphs of love over hate.

We are all sad for the country of Vietnam and the dispersion of the Sangha. The Abbot of Phuoc Hue, the Venerable Thai Thuan, cried and cried. Thay says these tears of love shall go down in the history books. Thay also shared that the Sangha has been more united by this experience than divided by the government’s actions. “The Bat Nha Sangha is already a legend in the history of Buddhism in Vietnam,” one which, I believe, we can allow to inspire and instruct for years to come.

Dear friends, it would be remiss of me to ask you to share your personal insight on the koan without sharing my own. So I will end with my reflections on this never-ending koan:

Compassion is the energy that protects. With compassion and nonviolence as our way of being, we discover non-fear and need not act from anger. Bat Nha is not a distant event, remote from our lives in the West, but a collective experience of our international community. We are in this together. As individuals and as countries we should protect our integrity so that we have the moral right to speak out and are free (from vested interest) to act. The brothers and sisters of Bat Nha used their time to prepare mentally and spiritually for what they knew would come. They made the very best of the present moment, enjoying every day of practice. We might do the same.

May your koan practice benefit all living beings. May all be well, peaceful, safe, and happy. May all attain enlightenment. No discrimination.