By Joan Halifax

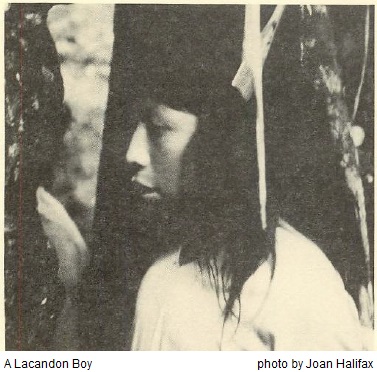

The Selva Lacandona of Chiapas, Mexico, is the second largest rainforest in the Western Hemisphere. In the 1940s, it covered more than 13,000 square kilometers. Today 3,312 square kilometers are preserved. Called the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, its presence has a profound effect on many aspects of our lives, including the weather in North America.

In February of 1992, twenty-five of us from different cultures walked into the heart of the Lacandon rainforest.

By Joan Halifax

The Selva Lacandona of Chiapas, Mexico, is the second largest rainforest in the Western Hemisphere. In the 1940s, it covered more than 13,000 square kilometers. Today 3,312 square kilometers are preserved. Called the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, its presence has a profound effect on many aspects of our lives, including the weather in North America.

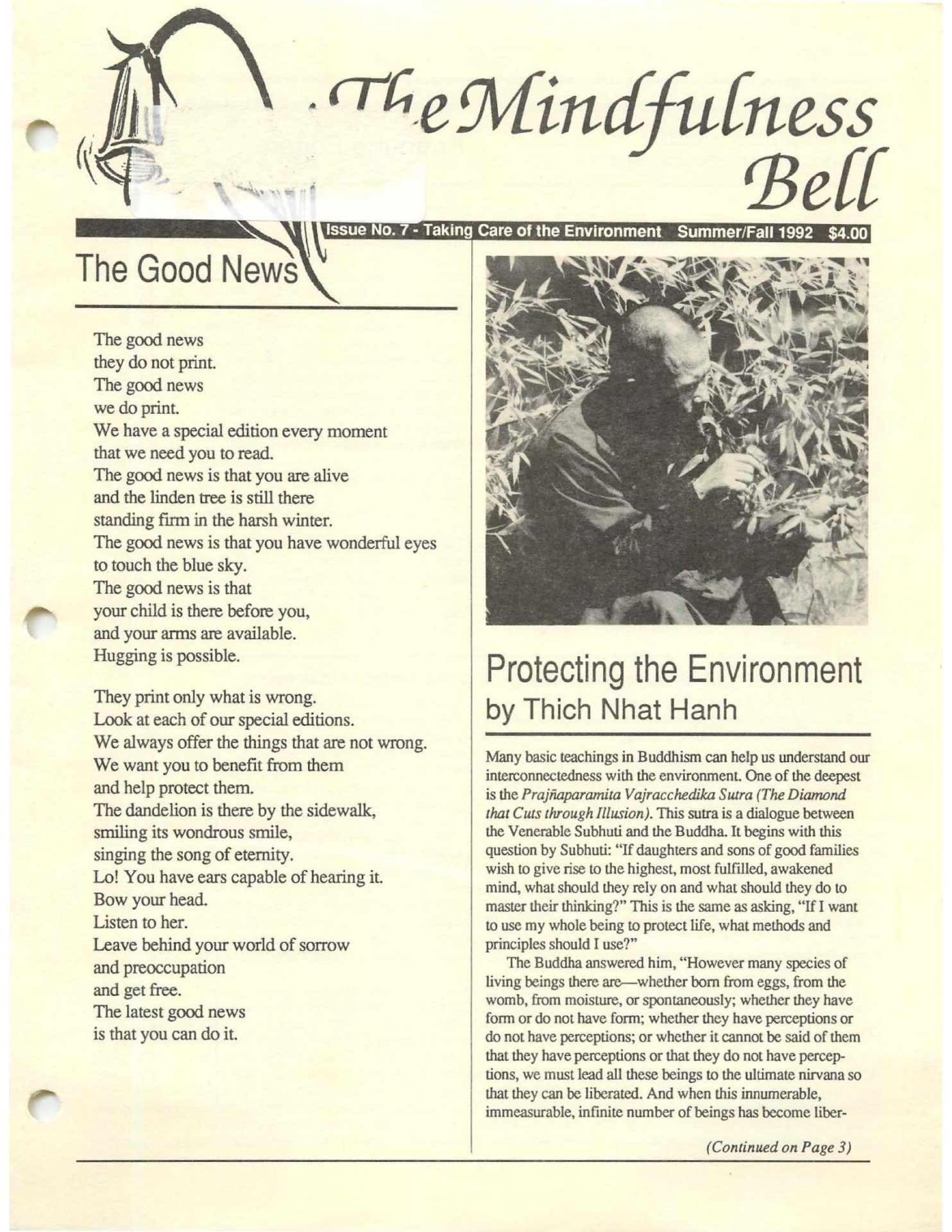

In February of 1992, twenty-five of us from different cultures walked into the heart of the Lacandon rainforest. The morning before we left, we all sat in meditation on a high deck overlooking the forest and fields near the archaeological site of Palenque. We could see patches of old, dark-green forest canopy spotted with flowers. We could also see large ravaged areas where cattle now graze. From the small "forest islands" that float in the expanse of clearcut fields, a profusion of butterflies filled the air, and we could hear small troops of howler monkeys.

At the end of the sitting practice, one member of the group offered this reminder: "We have nowhere to go, nothing to do." Keeping this in mind, we sorted our food and equipment and reduced our personal gear. Then we began the long, dusty drive through vast deforested areas to Lacanja, a Lacandon settlement on the edge of the great forest island now protected by the Mexican government. Most of us had fallen into silence as we looked at the naked landscape through which we passed. The three deadly sins to the forest—cattle, chainsaws, and cars—have for decades been in full force in this area. I kept remembering: "Nowhere to go; nothing to do." As we traveled by car over rough roads through the desolation, I also remembered the Japanese expression: mono no aware, "the slender sadness" that arises when we remember that no matter how hard we try, life consumes life, suffering is engendered through our very existence. Traveling to our basecamp, we go by car. This too contributes to the destruction of the forest, as Pemex, the national petroleum company of Mexico, continues its invasion of the region.

Finally, we stepped under the forest canopy. "Going nowhere," we took many steps, each one demanding our total attention. The floor of a tropical forest is a wild mass of tangled roots, the shallow soil inviting the great old trees not to penetrate but to spread and seek nourishment from the Earth's surface. We walked on no trails, animal trails, hunting trails, and horse trails as we humbly followed our two Lacandon Indian friends in their natural habitat. We were definitely out of our element. Walking required such complete attention that soon many of us fell into an absorbed if not desperate silence. The forest is a master teacher of mindful walking. One moment of wandering mind could mean a twisted ankle, a painful fall, a close and unwanted encounter with another species.

We swam in forest rivers, stood mute in clouds of butterflies, vividly scanned for snakes, and looked for signs of jaguar. Most of us never made peace with the insect population. In fact, as we stood in a circle before we left Lacanja and talked about our fears and concerns, insects were not mentioned. In the end, it was the tiny and powerful presence of biting insects that brought many of us to our knees (if not our ankles). Small things mean a lot in this forest world.

The forest also brought us to our senses. The day after we came out, most of us felt that we had been entered by the forest as we entered the forest. The forest was breathing us as we breathed it. As we made our way down the forest trails, the forest was making paths in us. Ten days later, as I met with friends and associates in New York City, I realized that I was still completely embedded in my sensory system. I felt wild and over awake, a house with all of its windows and doors wide open. Or to put it another way, I was at that moment adapting poorly to the ways of the city and civilization. Bringing the rainforest to the city in the form of milled mahogany is one thing. Bringing it in the atmosphere of the mind is something else again.

When we sat in council after our return from the Selva, we realized that more had transpired than we could have anticipated. On the side of "good works for other beings," the Lacandon Rainforest Protection Agency has now been created to be a bridge for researchers and students who want to enter the region. It is also raising funds for Ecosfera, an environmental research organization doing vital work in understanding and protecting the area.

In the heart of the Selva live Manuela and Pedro Sanchez and their large extended family. Over forty years ago, Pedro's father homesteaded the area. Now, Pedro and Manuela's seven sons, two of their daughters, and their offspring live and farm in what is now the center of a national park. Their domain is expanding and with the increase of the Sanchez family, the land they cultivate increases. The Mexican government wants them to leave. We explored another alternative with the Sanchez family. These Tzeltal men and women know the forest like they know their own hands. Since childhood, they have walked, explored, hunted, and farmed the area. They know the habitats and habits of the creatures. They know the location and usage of a vast number of plant species. They, like their Lacandon neighbors, are the true naturalists of the Selva. Our visit to their rancho was the first experiment on how their rancho can potentially become an educational and research center, their sons and daughters the hosts, naturalists and guides of the area. The Sanchez's life in the Selva may be preserved if they choose to work for the preservation of the forest.

We also worked for the reconciliation of the Sanchez family with their Lacandon neighbors, who are trying to protect their rights and hunting lands. When all of us enjoyed silence and prayer before shared meals, smoked the sacred pipe and entered the sweatlodge, sat in council (in four languages), or made our way collectively through the forest, it was clear that we wanted to live in a peaceful and caring way with each other. Our "experiment in community" was a new and unusual experience for our friends from the forest. And it was a model of a possibility for respectful communication, understanding, and compassion between cultures.

And for those of us who were shortly to travel north, as many questions came out of the journey as there were answers. On our second walking day, when I was alone on the trail, I stopped after an hour or so and stood still and silent in the wet green of old trees and young ferns. I felt for an instant that my whole body was covered with eyes. All of me wanted to see; wanted to know and understand. As I gazed into the forest, this simple question came to me. "What is seeing me that I am not seeing?" I was to carry this question throughout the many steps of the journey. I carry it still.

Joan Halifax is founder and director of the Upaya Foundation, Santa Fe, and a teacher in the Order of Interbeing.