By Claude Thomas

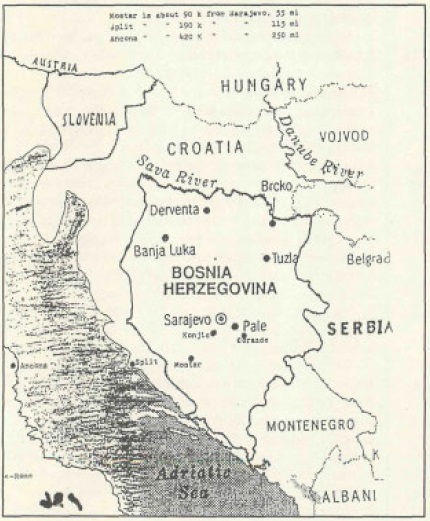

Vietnam veteran, Claude Thomas, was one of 20 participants in a nonviolent direct action project in Croatia and Bosnia from November 30 through December 20. The Sjeme Mira (“Seeds of Peace”) program included daily interfaith prayer services with elements from Buddhist, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim traditions. They distributed leaflets in English and Serbo-Croatian advocating to the people of the former Yugoslavia to abandon military force and instead work for justice using Gandhian nonviolent resistance. Mostar, a city they stayed in 90 kilometers south of Sarajevo, was under incessant sniper attacks and bombarded one day by a Croatian tank.

By Claude Thomas

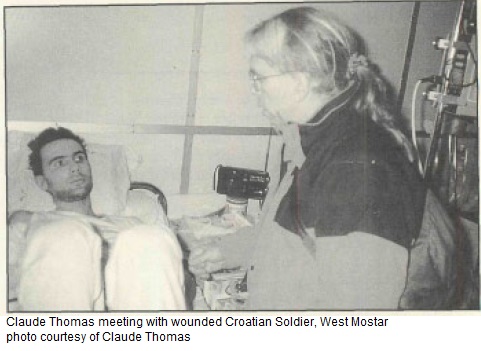

Vietnam veteran, Claude Thomas, was one of 20 participants in a nonviolent direct action project in Croatia and Bosnia from November 30 through December 20. The Sjeme Mira ("Seeds of Peace") program included daily interfaith prayer services with elements from Buddhist, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim traditions. They distributed leaflets in English and Serbo-Croatian advocating to the people of the former Yugoslavia to abandon military force and instead work for justice using Gandhian nonviolent resistance. Mostar, a city they stayed in 90 kilometers south of Sarajevo, was under incessant sniper attacks and bombarded one day by a Croatian tank. The project members distributed gifts of medical supplies and food to the residents.

It may be the first lime in history that leaflets advocating nonviolent resistance as a substitute for military force were distributed to both sides in a battle zone. It was also the first time a United Nations agency (the UN High Commissioner for Refugees) helped propagate the message of a peace project advocating that nonviolent resistance be substituted for military force. Claude had the opportunity to visit a wounded soldier in a hospital in West Mostar. What follows is an excerpt of their conversation:

Claude: Do you think there is any chance for peace?

Soldier: When years have passed, when people no longer remember the war, we might have peace. But as long as I'm alive and the people on the other side are alive, we will remember the war and all the pain we have suffered. There will always be doubts about the other side. We may live together, but we will never be able to trust each other.

Claude: In the last three years I have been living with Vietnamese people who were my enemy and now I am learning to be with them in a different way, to see them not as the enemy. But I understand about trust. I have to work very hard sometimes to trust.

Soldier: Many years have passed since the Vietnam War. I am wounded now. At the time you were wounded, all Vietnamese were your enemy, right?

Claude: Yes, that's true.

Soldier: From the children to the elderly.

Claude: Yes.

Soldier: Maybe in ten years, I will live with Muslims in peace and brotherhood, but I cannot do that now. It would be a lie. They captured me, tortured me, forced me to work. Yet the Muslim doctors saved my arm and treated me like a human being. But most of the ones on that side are savages.

Claude: You know, twenty years after the Vietnam War I still hadn't touched the wounds from that experience. Three years ago, some Vietnamese people invited me to come live with them. I feared they were going to bring me there to put me on trial and kill me for war crimes. I believed this, but I went there anyway. Because I somehow understood that it was important to heal, and not to hate.

Soldier: To heal yourself?

Claude: Yes. To heal myself because the healing starts here with me. As I heal, other people can experience my healing. So I came here to talk with you, to listen to you, to touch you.

Soldier: You can understand me like only one who has been through a war can.

Claude: It's true. Other people can see us with compassion.

Soldier: But they cannot understand.

Claude: We can help them understand by talking about our experience. It's important to talk about the war in a very real way, about our pain and suffering, so that our children will not have to go to war again.

Soldier: I would not talk to my children about the war. I would never tell them war stories or my involvement in this war. I would raise them as if war didn't exist. War is stupid. Physical force is a way that stupid people settle arguments. Later in their journey, members of Sjeme Mira visited a hospital in East Mostar. The following excerpts are from a journal Claude kept while in Mostar:

We took a very dangerous route, crossing several streets that were available to snipers. We were fired on at every intersection. The hospital's foundation was sandbagged and all the windows were blocked and protected as best as possible from shrapnel and sniper fire.

When we entered the hospital, the lights had gone out, so I spoke with the doctor in charge in a room lit by a small kerosene lamp. I carried a message from the Croatian soldier whom I talked with in a West Bank hospital. It was a message of gratitude and thanks to the Muslim doctors, his enemies, for saving his arm—a message well received by this doctor. It was important to hear "thank you," particularly from one's enemy. It touched humanity in an otherwise inhumane existence. In the dark, we walked to the intensive care unit. Our translator told us that most of the men there were soldiers. I was standing by the bed of one soldier who was severely wounded by a mortar blast. He had been hit in the stomach and his arms were seriously wounded. Standing by his bed, I concentrated on the sound of his labored breathing, unaware of anyone else in the room.

The lights came on and I saw this soldier lying in the bed in front of me. I remembered my own experience of being wounded, repaired, and how lonely and hard the recovery was. I transposed my situation onto the conditions presented before me. Standing in the intensive care unit, a former library, with beds jammed into the room with barely enough space to move, I felt for this young man suffering in complete darkness and isolation. I just cried. He spoke a bit of English, so we talked. After sharing our stories, we just looked at each other with an understanding beyond words.

What was common between us—this soldier, the Croatian soldier, and myself—was that we did not understand what our wars were about. We only understood that circumstances dictated we must fight, and we didn't see how to stop it. We said good-bye and parted. Walking down the hallway, I encountered another soldier on crutches who had lost his foot about midway up his shin. I asked him how it happened, and he said that it was from a mortar blast. As I talked with him, I remembered Jeff, a friend and Vietnam veteran from the U.S., who lost his entire leg during the war. I told him about Jeff.

We talked of peace, of not fighting. He tolerated my proposals of nonviolence. He even wanted them to come true but thought them highly improbable. The concept of just not fighting was too simple. Besides if you are a soldier here, you have money, food, a place to live, and a measure of prestige. If you are not a soldier you have little or nothing.

The weight of suffering in the hospital was affecting me deeply. I felt short of breath and was beginning to feel heavier and heavier. I felt like I needed to go outside and get some air. We left the hospital and headed back across the 30-40 meters of free-fire zone. Passing that safely, I asked our translator Draqi if he knew of a quiet place in the city. He chuckled and said, "Look around you, there is nothing. Such a place does not exist." I accepted what Draqi said but wondered if I had more time on my own if such a place could be located.

...Being here reminds me so much of my own combat-military experience. The lines for me become very fuzzy sometimes. A real difference is that now I do not carry a gun. There is a sameness that I feel between then and now, between Vietnam and Bosnia-Herzegovina. It is the reality that this is the same war; only the physical surroundings, faces, and climate are different. Sometimes these become fuzzy, too.

I ask myself again and again what can I do? And the answer comes back to me—be present, give witness, talk, listen deeply from that place of understanding beyond intellect. Dare to be present in the world in a way that seems to most extreme and radically different. Talk with soldiers on the front lines and the soldiers who have been trained to fight but have not yet pulled the trigger. Share my food, my time, my whole self with others.

I can't help but have a tremendous amount of hope that this conflict is resolvable; that the fighting will stop, and that the city will be rebuilt into the beautiful place that it was. But they need people like us coming regardless of the numbers that make it in.

Claude Thomas is a disabled combat veteran of the Vietnam War and a writer, who helps lead meditation retreats for veterans and others. Members of Sjeme Mira returned from Bosnia-Herzegovina in late December. Claude has been asked to return to continue his peacemaking efforts. Anyone interested in the work he is doing, please contact him at 321 Bedford St., Concord, MA 01742; (508) 369-6112.