Interview with Cheri Maples by Barbara Casey during the Hand of the Buddha Retreat, June 2002

Cheri, how did you decide to be a peace officer?

Cheri: There were three things I wanted to be as a little girl: a lawyer, a police officer and a professional baseball player. I really wanted to be a professional baseball player, but when I was growing up girls were certainly not cops or lawyers,

Interview with Cheri Maples by Barbara Casey during the Hand of the Buddha Retreat, June 2002

Cheri, how did you decide to be a peace officer?

Cheri: There were three things I wanted to be as a little girl: a lawyer, a police officer and a professional baseball player. I really wanted to be a professional baseball player, but when I was growing up girls were certainly not cops or lawyers, and even less professional baseball players. However, in addition to being a police officer, I am also a licensed attorney so two out of three is not bad.

I went to high school and college during the Vietnam War and like many other people in this country born in the 1950s, by my teenage years I had become somewhat of a "question authority" rebel. In my early twenties, I had my first exposure to the reality of community organizing work and working to get institutions to be more responsive to the people they served. I had two different jobs. In one, I was doing community organizing in the largest federal housing project in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and I was often the only white person in the building. The second was as an advocate for a first-offender's program for women convicted of prostitution. I was the only white woman on the staff. Through these two experiences, I learned how limited and "white" my view of the world was, including my thinking, seeing, and hearing. Both these experiences had a big impact on me.

I was working with people who didn't have any resources, which also had an impact on me. All of this work led me to think more about violence against women. Almost every single woman who had been referred to the prostitution program bad been a victim of a sexual assault at some time in her life. This motivated me to get more active in various efforts to end violence in the lives of women and children. I realized that though there were so many peace activists with good hearts, most people were not capable of making peace in their own homes.

I started volunteering with the Women's Coalition, an umbrella organization in Milwaukee that housed several different groups working on various women's issues. They sent me to training put on by community organizers from the Alinsky Institute in Chicago which was a tremendous training in grassroots organizing. I was also working on a master's degree in social work part time and commuted to Madison from Milwaukee once a week to attend classes. By 1979, I moved to Madison for a semester to finish my degree, but once I got there, I never left because the community was so much more progressive and so much more of a supportive atmosphere to live in as a lesbian.

I did my field placement for an organization called Dane County Advocates for Battered Women. It was a grassroots organization with a wonderful young and dedicated group of women working to provide some safe alternatives for women in abusive relationships. At the time, it was a huge job because there was so little consciousness about the issue. I worked there for a couple of years and became the Community Education Coordinator. In addition to doing training for police officers, hospitals, churches, and anybody else that would invite me, I started organizing groups of formerly battered women to help get legislation passed to provide state funding for shelters for battered women and their children.

I left that job to become the first director of the Wisconsin Coalition Against Woman Abuse. Wisconsin was trying to form a coalition of all the various service providers in the state and there were tremendous conflicts between service providers in different parts of the state. They received a grant that funded a paid staff position and I was hired. The organization grew and eventually became the Wisconsin Coalition Against Domestic Violence. I had the privilege of working with people from both urban and rural organizations who were very different from each other and were from every place on the political continuum from feminists on the left to very conservative people on the right.

I enjoyed that job very much and had the opportunity to put my community organizing skills to work building a coalition.

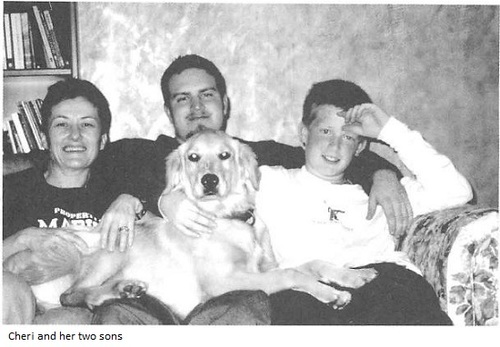

After two years of working there, my partner and I decided we wanted to have children. We each had one biological child and I am the proud parent of two sons, Jamie who is now nine teen, and Micah who is fourteen. It got very hard to support a family on a community organizer 's salary so I decided to return to school to get a Ph.D. in social work. I did the course work while working as a teaching assistant. In my last semester of course work, I realized I was not very comfortable being in academia fulltime. I grew up in a very poor, working-class family and I just was not very comfortable or happy in academia on a fulltime basis.

One of the field students that I had supervised when I worked at Dane County Advocates for Battered Women had become a police officer. She talked to me about becoming a police officer. She pointed out that although policing was really a type of social work that it was a male dominated profession and hence paid a lot better than any of the work I had been doing. The police chief at the time, David Couper, was very progressive and an anomaly as a police chief. Some referred to him as the socialist police chief of the Midwest. He was very progressive and interested in diversifying the police force. He had brought people of color on to the force and was very committed to bringing women into policing at a time when there were not any women working as police officers on the street.

I had a difficult time imagining myself in a paramilitary organization. I had worked mainly in grassroots organizations small enough to make decisions by consensus, so the contrast just seemed too great to me. I eventually decided to just go through the application process, which was very long. The interviews intrigued me because the questions they were asking me were about who I was as a person and how I communicated with people, not about my ability to use force. It was quite a decision to follow this career path because I had always worked outside the institutional system, trying to make it more responsive to people and had not been part of the system before.

A lot of people I had worked with were very angry with me. They thought I was making a wrong choice and that I was selling out. I was pretty divided about it myself. I almost quit while I was going through the police training academy. I was in very good shape physically I have always been very athletic but some of the attitudes of people whom I was going through the academy with really bothered me. However, my class was very diverse. There were two other lesbians in my class, about onethird of my class was women, and about one-fourth of the class shared values similar to mine. This was in 1984.

How were you women treated?

Cheri: There had been two or three classes of women before us, but many men did not accept women yet, and there were still lots of questions about whether women belonged in policing. With time, men started to see that women brought some positive things to policing, for instance that you could talk a person into handcuffs instead of using force to get people to comply with your requests. I believe they were just starting to see the value of interpersonal and communication skills in being an effective police officer and that women brought this style into policing much more often than men did. I don't think it was just a coincidence that women started coming into policing about the time that "community-oriented" policing began.

However, even once women started being accepted, the attitude toward lesbians was very hostile. When I went on my first field training experience, other officers (both men and women) were wearing "happily hetero" buttons and "straight as an arrow" buttons, and there was a big hubbub because the police chief ordered them to take them off.

When women first came on the force they had received pornography in the mail. It was very hard to get uniforms and equipment made for women; we were often walking around in men 's pants and shirts and bulletproof vests. All of that has changed. Sometimes a woman would respond to a call and if there were male officers with a hostile attitude who had arrived before her, they didn't want anything to do with her. Other times they would just sit in their car to see if she could handle a situation herself. People of color experienced the same thing as they were coming on to the police force. People were not very accepting in the beginning. There was a lot of racism, a lot of sexism, a lot of homophobia.

However, there was something refreshing about being with the other police officers. Unlike academia, where some people used politically correct language to hide their real biases and feelings, people in the police department were very honest about their attitudes, even in the early days. I appreciated that and it made it possible to communicate honestly.

When I began training it was hard because I was learning a job where my own safety, as well as the safety of others, was dependent on my ability to handle myself in volatile situations. When my life is on the line and my safety is an issue, I need to have the trust and support of people around me.

I went through what I'm sure people in the military go through. For example, for the first three months that I was working on the street, I had combat dreams just about every night. This really surprised me because I never felt consciously afraid. I don't know why, but even when I was in dangerous situations involving weapons or gunshots being fired, I never felt afraid at the time. I think we just learn to do our job and think about it afterward. However, I believe there is a type of a cumulative posttraumatic stress. For me, although fear was not a conscious issue, whether or not I was doing the right thing and whether or not being a police officer was right livelihood for me was always an issue. It was strange because even though I struggled with this, the job felt like a really good fit for me.

The first time I came to a retreat of Thay's, by the end of the retreat I really felt like I had come home. Becoming a police officer felt similar. Even with the challenging atmosphere, I felt like I had come home to something that was important and that I had never experienced anywhere else that I worked. And I had done some very challenging and very satisfying things. With time, I also began to enjoy the close relationships I formed with many of the men I worked with. As a lesbian there aren't all these romantic possibilities and sexual tensions getting in the way of real intimacy so my relationships with my male coworkers were often very, very close. Although it wasn't comfortable when a man didn't know that T was a lesbian and would ask me on a date, that did not happen too often. The intense homophobia, sexism, and racism that existed in the early '80s has definitely been transformed in my department. It has not disappeared but life is so different here now than when I first joined. What made this transformation possible was simply people really getting to know each other, working side by side, and piercing the stereotypes. There were all different levels of relationship issues that were going on that were hard and challenging to deal with. I'm really glad that I was thirty-one years old at the time and not trying to deal with these things at age twenty-two because it was hard enough at thirty-one.

How many years did you do police work before you came across Thay's teaching?

Cheri: l was a police officer for seven years before I went to my first retreat in 1991. By that time I was starting to understand that being a police officer was probably going to be a career for me rather than a transition to something else. T was working nights, on the "power" shift, 7 p.m. to 3 a.m., the overlapping shift with afternoons and evenings.

I had read a couple of Thay's books, which sparked my curiosity. In the spring of '91, l had a work injury and I sought treatment from a local chiropractor. I saw a registration form on the bulletin board in the waiting room for a retreat with Thich Nhat Hanh i n Mundelein, Illinois. I decided to check it out. Although Thay gave the Dharma talks at that retreat, the monastics led the Dharma discussions and discussions about the five precepts. (They were called precepts rather than mindfulness trainings at that time.) Sister True Emptiness (Sister Chan Khong) played a very large role at that retreat.

The first thing that caught my attention was that Thay's attitudes towards women and gay and lesbian people seemed so different from any spiritual leader I had ever been exposed to. He was so open and loving. His language was also gender neutral in that he used pronouns that were both male and female, which was still somewhat unusual at the time. I'll never forget a question someone asked him about how he felt about lesbian and gay relationships. I thought, "Here it goes, my bubble will be burst."

I didn't even want to hear the answer to the question because I was so sure I would be disappointed. Imagine my surprise when he said something like, the gender of the participants makes no difference, it's the quality of the love between the people that is important. I had very big fears of feeling like an outsider as both a lesbian and a cop at these types of gatherings. That dispelled one of my big fears, that I would be considered second-class as a lesbian.

However, as a police officer l usually felt like even more of an outsider at these types of gatherings. Most people attending Thay's retreats had progressive politics and many people with progressive politics automatically assume that police officers are the enemy. My partner, who attended the retreat with me, wanted to go to the discussion on the five precepts. I went with her but I felt that I could not even consider taking the precepts because of the requirement not to kill. As a person who carried a gun and who had a sworn duty to protect the lives of others, I knew that the possibility existed that I would have to kill some one to protect my own life or the life of another person. Even though I prayed I would never be in that position, I knew it was always a possibility that went with the profession.

At the discussion, I had a conversation with Sister True Emptiness that had a huge impact on me. She encouraged me to take the five precepts and challenged my assumption that I could not take them. She said something like, "Who else would we want to carry a gun except somebody willing to do it mindfully?" She was so supportive and wonderful and her logic was irrefutable. That conversation gave me some hope that it was possible to integrate my job with my spiritual aspirations.

I had never had the experience of the kind of silence, mindfulness, and slowing down that comes with the practice that I experienced at that retreat. Most of the retreat was in silence, and I felt so refreshed by the fourth or fifth day. I realized there was something about the practice that was really important. When I got back home and began making some initial efforts to practice, my energy slowly started to change. Although it was a gradual process and not something that happened overnight, I'm convinced it started at that retreat with my receiving the Five Mindfulness Trainings.

A lot of people at that retreat would not take the Five Mindfulness Trainings because they didn't want to give up alcohol and marijuana. It wasn't an issue for me because I was a recovering alcoholic and I bad been sober for a year. Shortly after I came back from the retreat I had a call involving a fifteen-year-old and a sixteen-year-old who had met a man at an Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meeting, who took them back to his house, got them drunk and sexually assaulted one of them. I was devastated. I had used AA as a real source of support; it was my introduction to spirituality. I could not believe that somebody would use it for that kind of personal gain. However, I knew that I was meant to be on this call. I spent the entire night and half the next day with the young woman who was sexually assaulted. I got her collected with her sponsor and a good support system and checked in with her occasionally over the next few months. I gave her a medallion that I had received as a gift for my six-month sobriety anniversary. I carried that medallion around all the time and I would take it out of my pocket and rub it whenever I was having a hard time. I told her to do the same thing. We have kept in contact and recently (ten years later) she came to my office to thank me for the support l gave her at such a difficult time. She is now married and has a beautiful two-year-old daughter.

I had other experiences after the retreat that showed me that the precepts were constantly working in my life. For instance, I had a domestic violence call in which my attitude toward the man involved before the retreat would have been: "you jerk." He was very angry and acting out his anger inappropriately. I could have arrested him for domestic disorderly conduct. Instead I got his wife and daughter out of the house and we were able to avoid any actual violence. Although he had intimidated and scared them, which is another form of violence, I could tell how hurt and scared he was beneath the anger and just sat there with him and talked to him until he started crying. Then, I held him, with my gun belt on and all. I would never have done that before it certainly isn't considered a "tactically sound" response. But, when you think about it, what could be a better antidote to an escalation of conflict? I could see and feel his pain. Three days later I was at an AA meeting, and this same man walked in. He pointed at me and said, "You! You saved me that night." And he gave me a big bear hug. Those kinds of events are so nourishing and reinforcing because you know you are really connecting with people.

I had a number of those experiences and I started enjoying being out on the street. I used to be in a hurry to finish one call and get to the next so other officers would not think I was slow. But after the retreat with Thay, I started taking the time to be with people wherever I was. I was much more compassionate in my work and as my energy changed and my demeanor softened so did the energy of people I was encountering on the street, even people I had to arrest. It was seldom necessary for me to use force after that. I am absolutely convinced that the energy you put out is what you get back, no matter who you're with. The anger and chip I carried around on my shoulder from a somewhat abusive and very neglectful childhood got much smaller and I slowly started the process of transforming the anger and rage I was walking around with.

And now you are in charge of personnel?

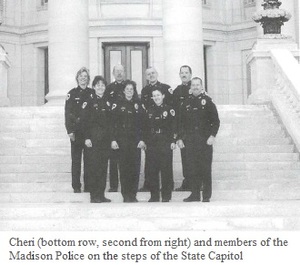

Cheri: I slowly went up the chain of command. I became a street supervisor, which is a sergeant, and then I became a lieutenant. As a lieutenant, I was the officer in charge of the night shift. Then I was a patrol lieutenant for a couple of years, then I was a detective lieutenant for a couple of years and now I'm the captain of personnel and training. I'm in charge of all the recruiting and hiring of police officers and the probationary training period of all the recruits while they are in the academy. We have our own academy that the police recruits are required to attend for seven months before they go out on the street, first with other officers, and then solo. I have a team of nine other people that I work with. I'm the top person in terms of rank, but we make decisions by consensus whenever possible, which is very unusual in a paramilitary organization. Every one of the officers on my team is great. We are also in charge of all the in-service training police officers are required to go through in order to maintain their law enforcement certifications. I do a lot of thinking about how to integrate the Five and the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings into the training we do.

When I was given this position, I immediately began managing my team in an alternative way. For instance, I don't control the budgets that I am responsible for; I give each supervisor on the team a budget and projects to be responsible for. We started with a two-day retreat held in my home where we built the philosophical foundation that we work and operate from. The essence of what I believe we need to do as a team is to inspire and enroll the recruits and other officers in possibilities through the training function. We have to show them and the rest of the organization that we create the community together. That it is not about what the people above them or below them are or aren't doing it is about what we are each doing as individuals and the community/family we create together. Ethics is now integrated into every single thing we teach. It's not a separate course anymore. We want recruits to understand that they are responsible for this family the Madison Police Family. We want them to understand that they have to be a reflection of the values of the organization in every interaction they have.

We take them on the ropes course (a physical training exercise involving teamwork) right away to get some cohesion formed in the group and then we lay a philosophical foundation. The new recruits need the support of their families when they are changing jobs so those family members also need to understand what is happening on the job. We began offering sessions with partners and family members, and started having the recruits do their own violence self-assessment as part of our domestic violence training. They also receive assessments and training on alcohol and other drug abuse. I am responsible for the domestic violence, community policing, diversity, and policy training they receive. I train as a team with people from different parts of the criminal-justice system, other service providers, and people in the community so they get several different perspectives.

The training team's function is to give the recruits the tools they need to effectively do their job. There are certain tools they need to have: they need to have crisis-intervention and mediation skills so they can deescalate a crisis; they need to have good communication and interpersonal skills. They have to know how to use a firearm and take care of themselves and others physically. Most important, they need to have good split-second decision-making skills.

I also try to help them understand that some of the skills we are teaching them as police officers (e.g., command presence, taking control) do not work well in interpersonal relationships. I try to help them learn to distinguish when these skills are useful and when they are not. If they can't do this, they will not make very good police officers, and they will make terrible partners, spouses, and parents. It's sometimes hard to turn it off and on and you may not even be aware of what you are doing, but they can't let this kind of attitude bleed into their home lives. Partners, friends, and family members need to understand this so they can help the officers know when this is happening. As police officers, we need the help and support of those around us to give us honest and loving feedback.

Those are some of the alternative things that we try to include in our training. We do a lot of enrolling people in possibilities in terms of getting them to think about what they want to be as human beings and how they want to interact with others on the planet. I want them to understand that the more open they are, the more likely they will be to perform this job with the open heart required to be effective. We get 900 applications for twenty-two positions, so I tell the recruits that I know they are all smart enough to do the job, but I don't know whether they have enough heart to do it.

Do you use listening skills in your training programs?

Cheri: We do training in listening skills and interpersonal skills not only in the recruit academy, but also in the leadership academy, which everyone who wants to be promoted must attend.

There's also lots of training involving listening skills in other areas. We do a big section of training on race and suspicion and the history of people of color in this country with law enforcement. We want people to understand that when someone says, "You're only arresting or stopping me because I'm black" or something like that, that there are very real reasons people feel that way. We try to get police officers to understand why people react like this and that it's not about them personally.

We teach a lot about conflict cycles and how they start. There's what is, and then there are our perceptions of what is, and most people collapse those two things continually without realizing it. We try to get them to think about how that happens for them internally and how it happens with the people they are encountering on the street, so they can stop the inevitable conflicts that lack of insight produces.

We do a lot of teaching about how to ''treat other people how they want to be treated but first find out how they want to be treated," because cultural differences can create misunderstandings if you just assume you know how someone else, especially from a different culture, wants to be treated. We do a lot of scenario training with both routine and high-intensity situations. All these activities include communication and listening skills. We try to balance the training between the community-oriented skills and the tactical skills they need to keep themselves and others safe.

I've also made a training team credo that is based on the Fourth Mindfulness Training. Right away I teach that gossip is a false form of intimacy. Don't let people tell you that only women gossip. I work in a predominantly male organization and it's a worse problem than I've ever encountered. It's like being in high school, except everyone wears a gun. I try to get the officers to talk directly to people rather than about them. It is very difficult, but as a staff, we keep bringing it up and asking ourselves how are we doing with it.

The other thing I try to get each of the staff and recruits to do is to live our mission statement and to think about their own personal mission statements. We have lunch together and talk about what our aspirations and motivations are, who we want to be. It's a very different way of doing business than the way it is done in most police departments. That is one of the advantages of going up the ranks to management. You get to be in charge of at least a slice of the pie.

One way of handling all the suffering that you have to deal with, day in and day out, is to close your heart. Do you have that problem?

Cheri: It's interesting that you say that because that's where I was at before this retreat. I was closed down and didn't even realize that there had been too much to take in. That's why I was in tears when I asked Thay the question about police officers.

There was so much emotion just sitting there. It's so important for us as police officers to examine this issue deeply. Closing down to people's suffering and becoming cynical because of so often seeing people at their worst can happen slowly over time without one even realizing it. I know I've changed and l have watched the people around me change. We have to do more as an organization to provide officers with the support they need not to allow this to happen. We currently operate on pretty superficial levels with the help we do provide.

I've also worked to offer mandatory crisis debriefings for everyone involved in stressful incidents. If it's not required, people often feel like wimps when they ask to go. The problem is that it's still up to a commander to identify those incidents. What one person considers usual business may have a horrifying effect on another. For example, when recruits get to their first car accident and see their first dead body or people with terrible injuries, they might need help with that. However, that's considered routine for people who have been on the job for a while.

Right before I left for this retreat a number of members of my Sangha approached me to ask how they can help support the police. One person is very interested in getting involved in restorative justice, in getting victims and perpetrators together to communicate and transform their suffering. Another wants to work with police officers and help them deal with the accumulated stress that can lead to a type of posttraumatic stress syndrome. Whatever support people can offer us, we'll take.

There's still so much for me to deal with that has come up at this retreat. l realize that I'm still not 100% comfortable with what l do, and Thay's Dharma talks and answer to my question were very helpful to me on this level. I want to discover new ways to stay honest with myself about what is going on internally.

Well, you are doing a huge job of bridging, and that is a key responsibility in our society, but often a lonely one.

Cheri: You just get so much crap; people see you as an enemy everywhere, and that's as hard as dealing with the suffering you see daily. You are seen as the bad guy by everybody, including poor people and people of color who are already exploited.

So, you are seen as the enemy both by people who want to help others and people who need the help of others. It gets hard to be the bad guy everywhere. Although 911 has certainly helped with this, it hasn't changed the stereotypes of cops much.

How does your Sangha support you, especially in those hard times? You must have days when you feel you've worked so hard and instead of acknowledgement you get the opposite.

Cheri: Never have I felt such support in my life as the support I get from my Sangha. Never have l gotten so many expressions of openness and offerings to share and communicate about my dilemmas. We meet on Tuesday and Friday nights; I hated to meet on Friday nights at first but now I love it because it's a door from my week to my weekend. I can't tell you what my Sangha means to me as support. They asked me to make a presentation on my work, and the discussion that followed was so healing for me. But I still struggle with whether I'm on the right stage. I am an anomaly as a police officer. There aren't many of us police officers interested in mindfulness. However, that is why I am so excited about Thay's commitment to do a retreat for us sometime in the future. It could be the start of a wonderful transformation in policing in this country.

I don't want to imply that there is anything wrong with what I'm doing; l feel I'm breathing life into the values of a democracy and the spirit of the law, and I'm proud of that. But some of the people I work with have no business being cops, and that's hard. There are so many cops across the country who not only have no business being cops because they are violent and corrupt, but the injustices they inflict affect the reputations of all of us. One of the things I do is to talk about how important it is that each of us uphold the responsibility we are invested with as the only people in society who have access to legal force.

Most of the time you're on your own, there's no one looking over your shoulder. It's a bureaucracy turned upside down because people at the bottom level make 99% of the decisions. Prosecutors and judges only see who we bring before them. If we don't make an arrest, they simply aren't aware of it. Supervisors within the organization also see very little of what actually takes place on the street. What's amazing to me is the amount of discretion we are given each moment in every situation. I'm convinced that police officers don't take credit for most of the good work they do. Ninety percent of what we do is deal with people who are in crisis who don't know who else to turn to, not the stuff you see on TV. People are out of touch with the reality of our work and we help perpetuate most of the myths.

Cheri, how would you like us members of the community to support police officers?

Cheri: I think the most important thing people can do is to give us the kind of encouragement that Sister True Emptiness gave me. The first real support outside of my family that I got for being a police officer was from Sister True Emptiness and the people in my Sangha. I have also felt incredible support from the larger Sangha here in Plum Village, which I am so grateful for. I can't tell you what it is like to feel I am with people who have values that I share on a deep political and spiritual realm and who support what do. It is important that we all provide that kind of encouragement and support for each other, which is exactly what Thay's Dharma talk on the different faces of love was all about (the Dharma talk published in this issue). We need mindful people in every conceivable area of society. All of us need to practice mindfulness so we have the awareness not to create damage in our relationships and our work.

As a police officer, as a parent, as a partner, I know that I have often played the role of both victim and oppressor. We need to offer each other the safety and support to talk openly and honestly about these things so we can learn from our own mistakes and the mistakes of others. Likewise, those of us working within the system need to support each other in doing the critical self-examination necessary to understand and identify the ways in which we have been coopted that we are blind to. We need to help each other stay on the path of working tenderly and lovingly on our edges. For example, when people see motives in me grounded in ambition rather than love and compassion, I want them to gently point it out to me. When people see me closing down and operating from that edge of anger, I want them to gently point it out to me. If we can do these types of things from a place of Jove without judging each other, we will have much to offer each other.

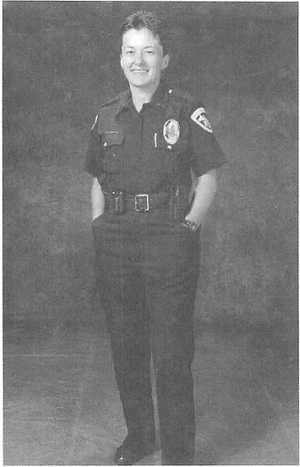

Cheri Maples, True Mindfulness Trainings, is a captain in the Madison, Wisconsin police force, supervising personnel training and recruiting.

In response to Cheri's request Thich Nhat Hanh will offer a retreat for law enforcement personnel from August 24-29, 2003 in Madison, Wisconsin. Anyone knowing of people who might be interested in attending, please email her at cmaples@ci.madison.wi.us